Okwei was a people-person, a trait that she used enormously to her advantage. Rising from having almost nothing to become the wealthiest woman in Nigeria, she built relationships with both native Nigerians and the British which led to her being crowned Omu, or Queen. Her political expertise and excellence in this position ensured that she would be the last to ever hold the title.

Okwei was the daughter of Prince Osuna Afubeho, a wealthy warrior. As was the practice of the time, Prince Osuna had many wives, all of whom were expected to provide for themselves through trade. Given that daughters were unable to inherit the property of their fathers, Okwei's mother insured that her daughter had a solid background in trade so that she would be able to provide for herself.

At age nine, Okwei was sent to be apprenticed to her maternal aunt in the Igala tribe. Nigeria was, and still is, a country with hundreds of tribes, each with unique languages and customs. At the time, the Igala language was very important for trade, and during her apprenticeship Okwei not only learned how to do business, but the language that would open a lot of doors for her. By the time she returned home at age fifteen, she was successfully trading in vegetables and poultry.

In 1889 Okwei married Joseph Allagoa, an influential brass trader. Okwei's family disapproved of the match, given that Joseph's family did not share the same royal status of Okwei's family. Okwei, however, didn't care, and married Joseph anyways, despite the fact that her family withheld her dowry.

The dowry was an important part of marriage for an Igbo woman of the time. Because women could not inherit their father's money and property their dowry was the only way for them to build up a successful trading business after marriage. A dowry was essential for being self sufficient, and for having a successful marriage. Marriages in which the wife was not successful in her trading endeavors, and in which she did not contribute to the family financially, rarely prospered.

Despite her lack of capital, Okwei started a business in palm oil trading--a highly lucrative product at the time. She was able to make use of her husband's business connections to start building her empire, and though they divorced not a year after marrying Okwei was able to use those contacts throughout her life.

Okwei and Joseph divorced in 1890, and Okwei had custody of their son, Frances. Okwei continued her trading business, and in 1895 married again, this time to Opene of Abo, the son of a successful and wealthy trader. Okwei's family once again disliked the match, this time because of Opene's lack of work ethic, and once again Okwei ignored their protests and married despite her lack of dowry. Opene's lackadaisical attitude towards working, and his willingness to support Okwei in her trading endeavors suited her just fine, and they, reportedly had a very happy marriage, having one son, Peter.

Shortly after her second marriage, Okwei went into business with her mother in law, Okwenu Ezewene. Though Okwei later dissolved their partnership, Okwei was able to add less perishable items to her inventory. During this time Okwei diversified her stock to include cotton goods and tobacco-items in particular demand.

By 1904, when Okwei dissolved her partnership with her mother in law and became an agent of the Royal Niger Trading Company, Okwei was making an astonishing amount of 400 tickets a month. The ticket system was put into place by the British colonial government because of a lack of universal currency in Nigeria at the time. Many tribes refused to trade in British pounds, preferring to trade in traditional cowrie shells or iron rods. British merchants, on the other hand, refused to accept cowrie shells and iron rods as payment. The ticket system was put into place as a compromise. Each ticket could be converted into a certain amount of oil or other goods, but ultimately amounted to about one pound sterling.

Okwei continued to grow her trading empire by starting to trade in clay and iron goods. She also grew her network of trade contacts by marrying off her maids and foster daughters to European shop owners, translators, and government officials. This, combined with her honest and open attitude, endeared her to Africans and Europeans alike.

The palm oil industry--Okwei's bread and butter--collapsed during World War One, as the main market for palm oil was in Germany. Okwei changed her trade focus from selling palm oil to selling ivory and coral beads. Ivory was valuable to Africans and Europeans alike--used for ornamental accents in Europe, and ceremonial jewelry in Africa. Okwei not only exported and sold ivory, but she also amassed a large selection of ceremonial ivory jewelry which she rented out for a profit.

In 1918 the ticket system was abolished, and a new currency--neither pound sterling nor cowrie shell--was introduced. By this time the Nigerians had started to trust the old currency (the pound sterling), and were suspicious of the new money. Because the British paid them in new currency Nigerians turned to money changers to buy goods locally. Okwei set up a business as a money changer, taking advantage of local suspicion to pay two shillings of old currency for every five shillings of the new.

In addition to money changing, Okwei also set herself up as a landlady and a money lender. She owned some sixteen houses--fifteen of which she rented out. She provided business loans to local businesswomen, and invested in her local market. Her vast wealth also made it possible to import goods directly from England--a costly and risky venture made less risky by Okwei's vast fleet of personal trading trucks and canoes.

While she was certainly a shrewd businesswoman, Okwei was also a respected member of the community, and the core of her family. She supported her sons and their wives in their endeavors, and was often the calm, impartial mediator in family disputes. She was devoted to her traditional way of life, refusing to become a Christian and keeping up her devotion to her native religion. This, along with her support for tribal government led to her being elected Omu.

The Igbo system of government at the time consisted of an unrelated king and queen. The king was in charge of the men, foreign relations, and most warfare, while the queen was in charge of the women, the economy, and the markets. Both were appointed positions, usually given to people who were greatly respected. Okwei took her duties as Omu very seriously, and was such a good Omu that the title has never been awarded to another woman out of respect for her legacy.

Much like Andrew Carnegie or J.D. Rockefeller, Okwei rose from poverty to become a millionaire. It would be easy to classify her as a captain of industry because of the money she poured back into her community, or as a robber baron because of the high interest rates she charged her debtors, but in reality she falls somewhere in the middle. While her methods were not always ethical, Okwei contributed enormously to the Nigerian economy, and helped pave the way for the modern female entrepreneur in Nigeria.

Sources

Omu Okwei, The Merchant Queen of Ossomari--a Biographical Sketch by Felicia Ekejiuba

Women in the Economy of Igboland, 1900 to 1970: A Survey by Gloria Chuku

Okwei of Ossomari (1872-1943)

| Okwei surrounded by her family |

At age nine, Okwei was sent to be apprenticed to her maternal aunt in the Igala tribe. Nigeria was, and still is, a country with hundreds of tribes, each with unique languages and customs. At the time, the Igala language was very important for trade, and during her apprenticeship Okwei not only learned how to do business, but the language that would open a lot of doors for her. By the time she returned home at age fifteen, she was successfully trading in vegetables and poultry.

In 1889 Okwei married Joseph Allagoa, an influential brass trader. Okwei's family disapproved of the match, given that Joseph's family did not share the same royal status of Okwei's family. Okwei, however, didn't care, and married Joseph anyways, despite the fact that her family withheld her dowry.

|

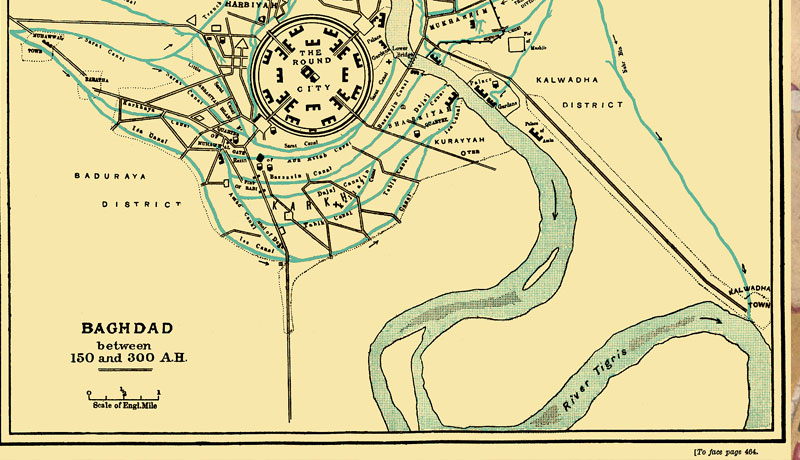

| Tribal and linguistic divisions of Nigeria |

Despite her lack of capital, Okwei started a business in palm oil trading--a highly lucrative product at the time. She was able to make use of her husband's business connections to start building her empire, and though they divorced not a year after marrying Okwei was able to use those contacts throughout her life.

Okwei and Joseph divorced in 1890, and Okwei had custody of their son, Frances. Okwei continued her trading business, and in 1895 married again, this time to Opene of Abo, the son of a successful and wealthy trader. Okwei's family once again disliked the match, this time because of Opene's lack of work ethic, and once again Okwei ignored their protests and married despite her lack of dowry. Opene's lackadaisical attitude towards working, and his willingness to support Okwei in her trading endeavors suited her just fine, and they, reportedly had a very happy marriage, having one son, Peter.

Shortly after her second marriage, Okwei went into business with her mother in law, Okwenu Ezewene. Though Okwei later dissolved their partnership, Okwei was able to add less perishable items to her inventory. During this time Okwei diversified her stock to include cotton goods and tobacco-items in particular demand.

|

| Unprocessed palm oil |

Okwei continued to grow her trading empire by starting to trade in clay and iron goods. She also grew her network of trade contacts by marrying off her maids and foster daughters to European shop owners, translators, and government officials. This, combined with her honest and open attitude, endeared her to Africans and Europeans alike.

|

| Cowrie shells-the traditional currency of the Igbo |

In addition to money changing, Okwei also set herself up as a landlady and a money lender. She owned some sixteen houses--fifteen of which she rented out. She provided business loans to local businesswomen, and invested in her local market. Her vast wealth also made it possible to import goods directly from England--a costly and risky venture made less risky by Okwei's vast fleet of personal trading trucks and canoes.

While she was certainly a shrewd businesswoman, Okwei was also a respected member of the community, and the core of her family. She supported her sons and their wives in their endeavors, and was often the calm, impartial mediator in family disputes. She was devoted to her traditional way of life, refusing to become a Christian and keeping up her devotion to her native religion. This, along with her support for tribal government led to her being elected Omu.

|

| The Onitsha market--still located on the land leased out by Okwei. |

Much like Andrew Carnegie or J.D. Rockefeller, Okwei rose from poverty to become a millionaire. It would be easy to classify her as a captain of industry because of the money she poured back into her community, or as a robber baron because of the high interest rates she charged her debtors, but in reality she falls somewhere in the middle. While her methods were not always ethical, Okwei contributed enormously to the Nigerian economy, and helped pave the way for the modern female entrepreneur in Nigeria.

Omu Okwei, The Merchant Queen of Ossomari--a Biographical Sketch by Felicia Ekejiuba

Women in the Economy of Igboland, 1900 to 1970: A Survey by Gloria Chuku

Okwei of Ossomari (1872-1943)