An extremely popular writer both in her lifetime and in the millenia since, Murasaki Shikibu is credited as writing the world's first novel, The Tale of Genji. A mysterious figure, Murasaki used her illicit knowledge of classical Chinese and Japanese literature not only redefine the genre she wrote in, but to create an artform that survives to this day.

Like so many of the women we cover, it's unknown if Murasaki Shikibu is even this woman's real name. Probably born in 973 CE, Murasaki not only grew up in a time where the early lives of women weren't deemed worth recording, but in a society where it was considered impolite to use a person's real name. The name we know her by is taken from her father's profession, and the name of the central female character from her novel.

Murasaki was the daughter of Fujiwara no Tametoki, a scholar, and lowranking member of the dominant Fujiwara clan. Murasaki's grandfather and great grandfather had both been important poets, and education was highly valued in her family. Consequently, her brothers were both given brilliant educations in both Chinese and Japanese literature. It was uncommon for ladies to be educated this way, as the Chinese language was considered to be unladylike. However, Murasaki showed an eagerness and aptitude for learning, with some stories even saying that she would eavesdrop on her brothers lessons through a door. Recognizing her aptitude, or perhaps tired of her antics, Murasaki's father allowed her to be taught in Chinese language and literature, grousing that such a mind was wasted on a girl.

In 998 Murasaki married family friend (and literal family) Fujiwara no Nobutaka. He was about twenty years her senior, and already had a basketball team's worth of wives, and an American football team's worth of children. As was traditional, Murasaki continued to live with her father after her marriage. Nobutaka must have visited at least once, however, because in 999 Murasaki gave birth to a girl she named Kenshi. Nobutaka died a few years later in 1001 when a plague swept Kyoto.

Whether or not Murasaki's marriage was a happy one is an interesting question. Japanese tradition paints her as a loving wife and loyal widow, but her writing brings all of this into question. There are certain resemblances between the idyllic Genji and an exiled nobleman of Murasaki's acquaintance whom Murasaki was rumored to have a relationship with. It is questioned if some of the love poems written by Murasaki might be inspired by this nobleman, and if the image of her as a loyal widow might be the moralistic construct of a later era.

After her husband's death Murasaki joined the court of Empress Shoshi as a lady-in-waiting. At the time the worth of a Japanese noblewoman was measured not by her looks, but by her artistic abilities. Being able to write sensitive poems, having beautiful calligraphy, and skillfully matching colors for the elegant draping sleeves of a kimono, was how a lady attracted a man. The sign of a successful Empress was the ability to surround herself with the greatest creative minds, much like the salon of Europe. By the time of her arrival at court Murasaki was already an accomplished poet. She had, however, made no forays into prose.

It is, of course, likely, that Murasaki simply woke up one day and decided to write a series of stories about the amorous adventures of a handsome nobleman, but the popular legend is much more exciting. In an episode similar to the gathering of Romantics at Lake Geneva, the Empress Shoshi lamented that there were no good stories, that she was tired of the old romances, and would Murasaki please write a new one. Murasaki agreed, and retreated to a Buddhist temple on Lake Biwa. One night while looking at the moon and lamenting the death of her late husband Murasaki was struck by inspiration, and wrote two whole chapters of her work on the back of sacred Buddhist texts.¹

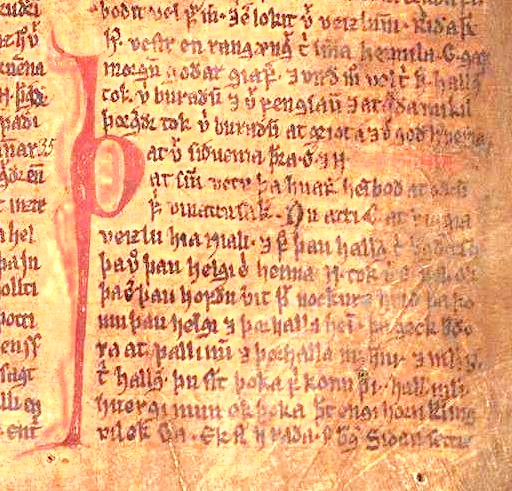

Genji was an instant hit. It was read by the Empress, and subsequently devoured by all the ladies of the court. This was unsurprising, as monogatari novels were as popular in Heian Japan as romance novels are today. Works like this were written in the fledgling kana, or written Japanese, and were thus accessible to women who were rarely taught Chinese kanji. What is surprising, is that men read Genji too. Empress Shoshi's father, Fujiwara no Michinaga, was an important court influencer, the real power behind the throne, and an avid Tale of Genji fanboy. From him the story circulated through the men of the court until noted male poets were congratulating Murasaki on her creation.

Murasaki, unfortunately, wasn't much for life at court. Conservative and introverted, Murasaki detested the inane frivolity and illicit love affairs that made up the daily schedule in the Heian court. She was often viewed as cold and aloof by her contemporaries, and had open rivalries with several other important female poets of the day. When Empress Shoshi left court after the death and abdication of her husband in 1011, Murasaki left with her.

The end of Murasaki's life was quiet. She died some time between 1014 and 1031, either staying with Shoshi to the end, or retiring to a Buddhist convent. She left behind a daughter, and an enormously popular work twice the length of War and Peace.

The Tale of Genji is perhaps the most important piece of Japanese literature. Its glimpses into the life of aristocratic Heian Japan are not only precious from a historical perspective, but the slice of life narrative and overarcing character development make it a literary gem as well. Additionally, Genji was a major factor in the standardization of kana, and became required study for anyone hoping to become a scribe.

The novel was copied out hundreds of times, and when woodblock printing came around it was distributed even further beyond aristocratic circles. It experienced a huge resurgence in popularity during the Edo period of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and owning a piece of Genji 'fanart' was considered the height of sophistication. This popularity continues to this day, with The Tale of Genji being translated over and over again, and being treated to reimaginings in a variety of mediums in and out of Japan.

¹This writing on the back of sacred texts wasn't seen as sacrilege like it would have been if written on a Bible, Torah, or Koran. Instead, this was used to justify reading The Tale of Genji to later audiences who had religious scruples about the content.

Sources

A History of Japanese Literature by William George Aston

Beyond The Tale of Genji: Murasaki Shikibu as Icon and Exemplum in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Popular Japanese Texts for Women by Satoko Naito

Murasaki Shikibu: Japanese Courtier and Author

Murasaki Shikibu: the Brief Life of a Legendary Novelist

Murasaki Shikibu-Tales of Genji

Murasaki Shikibu-New World Encyclopedia

Murasaki Shikibu-Famous Inventors

World Changing Women-Murasaki Shikibu

Summary of The Tale of Genji

Tale of Genji

The Tale of Genji: Work by Murasaki

The Tale of Genji

Historical Background

Background of The Tale of Genji

The Tale of Genji (Genji Monogatari)

In Celebration of The Tale of Genji, the World's First Novel

|

| Murasaki |

Murasaki was the daughter of Fujiwara no Tametoki, a scholar, and lowranking member of the dominant Fujiwara clan. Murasaki's grandfather and great grandfather had both been important poets, and education was highly valued in her family. Consequently, her brothers were both given brilliant educations in both Chinese and Japanese literature. It was uncommon for ladies to be educated this way, as the Chinese language was considered to be unladylike. However, Murasaki showed an eagerness and aptitude for learning, with some stories even saying that she would eavesdrop on her brothers lessons through a door. Recognizing her aptitude, or perhaps tired of her antics, Murasaki's father allowed her to be taught in Chinese language and literature, grousing that such a mind was wasted on a girl.

In 998 Murasaki married family friend (and literal family) Fujiwara no Nobutaka. He was about twenty years her senior, and already had a basketball team's worth of wives, and an American football team's worth of children. As was traditional, Murasaki continued to live with her father after her marriage. Nobutaka must have visited at least once, however, because in 999 Murasaki gave birth to a girl she named Kenshi. Nobutaka died a few years later in 1001 when a plague swept Kyoto.

Whether or not Murasaki's marriage was a happy one is an interesting question. Japanese tradition paints her as a loving wife and loyal widow, but her writing brings all of this into question. There are certain resemblances between the idyllic Genji and an exiled nobleman of Murasaki's acquaintance whom Murasaki was rumored to have a relationship with. It is questioned if some of the love poems written by Murasaki might be inspired by this nobleman, and if the image of her as a loyal widow might be the moralistic construct of a later era.

|

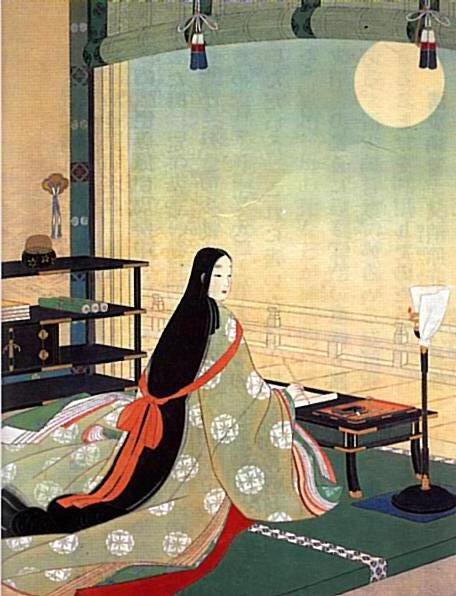

| Paintings capturing the moment Murasaki conceived Genji on Lake Biwa were very popular. |

It is, of course, likely, that Murasaki simply woke up one day and decided to write a series of stories about the amorous adventures of a handsome nobleman, but the popular legend is much more exciting. In an episode similar to the gathering of Romantics at Lake Geneva, the Empress Shoshi lamented that there were no good stories, that she was tired of the old romances, and would Murasaki please write a new one. Murasaki agreed, and retreated to a Buddhist temple on Lake Biwa. One night while looking at the moon and lamenting the death of her late husband Murasaki was struck by inspiration, and wrote two whole chapters of her work on the back of sacred Buddhist texts.¹

Genji was an instant hit. It was read by the Empress, and subsequently devoured by all the ladies of the court. This was unsurprising, as monogatari novels were as popular in Heian Japan as romance novels are today. Works like this were written in the fledgling kana, or written Japanese, and were thus accessible to women who were rarely taught Chinese kanji. What is surprising, is that men read Genji too. Empress Shoshi's father, Fujiwara no Michinaga, was an important court influencer, the real power behind the throne, and an avid Tale of Genji fanboy. From him the story circulated through the men of the court until noted male poets were congratulating Murasaki on her creation.

Murasaki, unfortunately, wasn't much for life at court. Conservative and introverted, Murasaki detested the inane frivolity and illicit love affairs that made up the daily schedule in the Heian court. She was often viewed as cold and aloof by her contemporaries, and had open rivalries with several other important female poets of the day. When Empress Shoshi left court after the death and abdication of her husband in 1011, Murasaki left with her.

|

| Also Murasaki |

The Tale of Genji is perhaps the most important piece of Japanese literature. Its glimpses into the life of aristocratic Heian Japan are not only precious from a historical perspective, but the slice of life narrative and overarcing character development make it a literary gem as well. Additionally, Genji was a major factor in the standardization of kana, and became required study for anyone hoping to become a scribe.

The novel was copied out hundreds of times, and when woodblock printing came around it was distributed even further beyond aristocratic circles. It experienced a huge resurgence in popularity during the Edo period of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and owning a piece of Genji 'fanart' was considered the height of sophistication. This popularity continues to this day, with The Tale of Genji being translated over and over again, and being treated to reimaginings in a variety of mediums in and out of Japan.

¹This writing on the back of sacred texts wasn't seen as sacrilege like it would have been if written on a Bible, Torah, or Koran. Instead, this was used to justify reading The Tale of Genji to later audiences who had religious scruples about the content.

A History of Japanese Literature by William George Aston

Beyond The Tale of Genji: Murasaki Shikibu as Icon and Exemplum in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Popular Japanese Texts for Women by Satoko Naito

Murasaki Shikibu: Japanese Courtier and Author

Murasaki Shikibu: the Brief Life of a Legendary Novelist

Murasaki Shikibu-Tales of Genji

Murasaki Shikibu-New World Encyclopedia

Murasaki Shikibu-Famous Inventors

World Changing Women-Murasaki Shikibu

Summary of The Tale of Genji

Tale of Genji

The Tale of Genji: Work by Murasaki

The Tale of Genji

Historical Background

Background of The Tale of Genji

The Tale of Genji (Genji Monogatari)

In Celebration of The Tale of Genji, the World's First Novel

/erik-the-red-detail-58b9732c3df78c353cdc45b9.jpg)