What do Napoleon, the son of a French lawyer, and being kind to prisoners of war have to do with the Swedish monarchy? Significantly more than you would think. In 1810, Jean Baptiste Bernadotte was elected Prince Royal of Sweden, and eight years later became the founding king of the dynasty that rule Sweden to this day, proving that, contrary to what Michael Palin said, sometimes you do vote for a king.

To understand the Bernadotte's rise to power, you have to understand late eighteenth century Europe. In the summer of 1789, Louis XVI, an absolute monarch from a long line of absolute monarchs attempted to solve his financial issues using the nominal democratic system France already had in place. This went poorly, and resulted in the common people calling for a new constitution, taking the Bastille, forcing Louis and his family from their opulent home in Versailles, and culminated in a lot of very wealthy and important people losing a very important appendage to the guillotine. "What does this have to do with the price of meatballs in Sweden", you ask? Well, the act of dethroning and de-heading Louis, scion of the long and noble line of Bourbon, sent a shock across Europe. After all, if the French monarch could be thrown out of power, and a 'democracy' instituted in less than two years, were any of the other absolute monarchs of Europe safe?

With the English kicked out of their American colonies, and the French monarchy quite literally headless, it seemed that the age of the 'enlightened despot', or the benevolent philosopher dictator was coming to an end. This was particularly worrying to the Swedish king Gustav III who was a great admirer of Marie Antoinette. He was a little more politically savvy than Louis XVI, and he survived his initial summoning of the Riksdag--or the (at the time) nominal Swedish democratic system. However, he made enemies, and bit a bullet Abraham Lincoln style in 1792.

Gustav III left his throne to his thirteen year old son, Gustav IV, or Gustav Adolf. The years in which Gustav IV's uncle served as regent were the best of his reign. Gustav Adolf grew into a paranoid and arrogant king, which lead to him losing Finland, Pomerania, and the Aland islands. He was forced to abdicate, and handed the throne to his uncle, Charles XIII.

Charles XIII wasn't so much the best choice for king as he was the only choice for king. The House of Vasa had been struggling since the abdication of Queen Kristina in 1654, and Charles had only tenuous claims to the throne himself. Furthermore, Charles was childless and a bit senile. It was clear to Charles and the ruling class of Sweden that if they wanted to continue to have a monarchy, they would have to elect somebody. The year was 1809.

Now, the 'election' of a monarch wasn't an uncommon thing, the Vasa's themselves had been elected. In cases where a royal line was dying out without an heirs, or in the case of creating an entirely new country, the nobility of a country would take a look at all the princes of Europe, and see who they liked. This sort of thing had been happening since medieval times, and in the tumultuous world of nineteenth century Europe, it was nothing to balk at.

Two distant cousins of Charles XIII were nominated as heirs, but one was an idiot, and the other died. There was a whole host of unsuitable candidates for Crown Prince of Sweden, and a significant portion of the Riksdag were sick of it. They wanted a successful monarch, someone who wasn't an idiot who would lose Finland. And who was more successful than the plucky young Corsican ruling France?

There was no way in hell that any self respecting Swede was going to invite Napoleon to be their king--they were an independent country after all. But maybe one of his brothers, or one of his Marshals, the military geniuses who had won Napoleon his vast empire.

Enter Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte. A commoner from Southern France, he ran away from his apprenticeship as a lawyer at age eighteen to join the French army. Like Napoleon, he had used the chaos of the French Revolution to rise rapidly through the ranks, eventually becoming a general. He supported Napoleon on his campaigns, eventually being made the French Minister of War, a Marshal, and then the Prince of Ponte-Corvo, a small principality in Italy.

Bernadotte was an attractive candidate for a number of reasons. He was a proved general, a proved administrator, and he already had an heir. He was extremely popular in Sweden, having received and made peace with Swedish officers independently of Napoleon's commands. He was also unemployed, which was very convenient for the Swedes.

Most importantly, he had been kind to the right person back in the day. Baron Otto Morner was about to become the brother-in-law to the Swedish Chancellor, and he was a big fan of Bernadotte. Bernadotte had been a major player in the Battle of Lubeck, during which Bernadotte and the French had roundly kicked Prussian and Swedish ass, but, like, nicely. Bernadotte captured a contingent of Swedish soldiers, and was so nice to them that Otto Morner was still a huge Bernadotte stan four years later. While in Paris, Morner brought the proposition to Bernadotte, who was incredulously flattered.

There was a lot going against Jean Baptiste Bernadotte however, and he knew it. He didn't speak Swedish, he wasn't Lutheran, and all of this was seemingly happening behind Napoleon's back. Napoleon and Jean Baptiste had never been great friends, and they certainly weren't bosom friends at the time, but Bernadotte said that the religion and the language thing could be fixed easily, and that, should Emperor Napoleon and King Charles agree, he would be happy to have his name up for consideration.

There was a hiccup. Morner hadn't been acting entirely officially. He was just a lieutenant, not an ambassador. An ambassador had, in fact, been sent to Napoleon, asking him on his opinion on who should succeed Charles XIII. Napoleon had backed King Frederick VI of Denmark-Norway, hoping to unite Scandinavia under a friendly flag. When he found out that Jean Baptiste had been offered the position, he wasn't crazy about Bernadotte being on the Swedish throne, but he loved the idea of a Frenchman on the throne. He went to his ex-stepson, Eugene, the Viceroy of Italy, and offered the position to him. Eugene refused. Napoleon decided to, well, not support Bernadotte, because if Bernadotte failed it would be embarrassing for Napoleon, but he wasn't not not supporting Bernadote.

Jean Baptiste discussed it with his wife, and after getting Napoleon's 'do it if you want', formally submitted his name for consideration. Baron Morner was an enthusiastic hype-man, campaigning for Bernadotte much like how modern pundits campaign for elected officials. Though there was a significant faction in favor of Frederick VI, and King Charles still wanted to elect his idiot cousin, Jean Baptiste was elected unanimously.

There were a few hurdles that had be overcome before Jean Baptiste could become Prince Royal, however. He had to become a Lutheran, that was non-negotiable. He also had to promise not to give any Swedish posts to Frenchmen, and allow Charles XIII to adopt him. Jean acceded, and took the name Charles John, becoming king Charles John XIV, or Carl Johann XIV to the Swedes.

The new Charles was good to his word, and any worries of a French takeover of Sweden were assuaged for good in 1813 when Charles and Swedish forces joined the sixth coalition to fight against Napoleon. Charles was Crown Prince for about eight years, from 1810 to 1818. During this time, he conquered Norway, and unified Sweden and Norway again. By the time he became King, he had thoroughly won over his new people.

Jean Baptiste Bernadotte's legacy lives on today in the ruling family of Sweden. The current king, Carl Gustav XVI is the great, great, great, great grandson of Jean Baptiste. When Carl Gustav's daughter, Crown Princess Victoria, becomes Queen Regnant, she will be the eighth Bernadotte monarch.

Sources

Bernadotte: Napoleon's Marshal, Sweden's King by Alan Palmer

Karl Johann XIV-King of Norway and Sweden

Charles XIV, King of Sweden and Norway

The Bernadotte Dynasty

The House of Bernadotte

Charles John XIV, King of Sweden and Norway

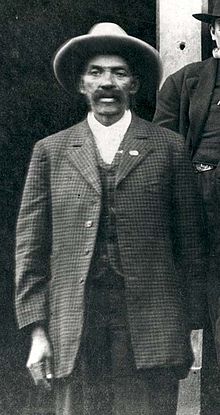

|

| Jean Baptiste Bernadotte, the hero of our tale. |

With the English kicked out of their American colonies, and the French monarchy quite literally headless, it seemed that the age of the 'enlightened despot', or the benevolent philosopher dictator was coming to an end. This was particularly worrying to the Swedish king Gustav III who was a great admirer of Marie Antoinette. He was a little more politically savvy than Louis XVI, and he survived his initial summoning of the Riksdag--or the (at the time) nominal Swedish democratic system. However, he made enemies, and bit a bullet Abraham Lincoln style in 1792.

|

| Gustav III |

Charles XIII wasn't so much the best choice for king as he was the only choice for king. The House of Vasa had been struggling since the abdication of Queen Kristina in 1654, and Charles had only tenuous claims to the throne himself. Furthermore, Charles was childless and a bit senile. It was clear to Charles and the ruling class of Sweden that if they wanted to continue to have a monarchy, they would have to elect somebody. The year was 1809.

Now, the 'election' of a monarch wasn't an uncommon thing, the Vasa's themselves had been elected. In cases where a royal line was dying out without an heirs, or in the case of creating an entirely new country, the nobility of a country would take a look at all the princes of Europe, and see who they liked. This sort of thing had been happening since medieval times, and in the tumultuous world of nineteenth century Europe, it was nothing to balk at.

Two distant cousins of Charles XIII were nominated as heirs, but one was an idiot, and the other died. There was a whole host of unsuitable candidates for Crown Prince of Sweden, and a significant portion of the Riksdag were sick of it. They wanted a successful monarch, someone who wasn't an idiot who would lose Finland. And who was more successful than the plucky young Corsican ruling France?

|

| Bernadotte again |

Enter Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte. A commoner from Southern France, he ran away from his apprenticeship as a lawyer at age eighteen to join the French army. Like Napoleon, he had used the chaos of the French Revolution to rise rapidly through the ranks, eventually becoming a general. He supported Napoleon on his campaigns, eventually being made the French Minister of War, a Marshal, and then the Prince of Ponte-Corvo, a small principality in Italy.

Bernadotte was an attractive candidate for a number of reasons. He was a proved general, a proved administrator, and he already had an heir. He was extremely popular in Sweden, having received and made peace with Swedish officers independently of Napoleon's commands. He was also unemployed, which was very convenient for the Swedes.

Most importantly, he had been kind to the right person back in the day. Baron Otto Morner was about to become the brother-in-law to the Swedish Chancellor, and he was a big fan of Bernadotte. Bernadotte had been a major player in the Battle of Lubeck, during which Bernadotte and the French had roundly kicked Prussian and Swedish ass, but, like, nicely. Bernadotte captured a contingent of Swedish soldiers, and was so nice to them that Otto Morner was still a huge Bernadotte stan four years later. While in Paris, Morner brought the proposition to Bernadotte, who was incredulously flattered.

|

| Jean's wife, Desiree Clary. She and Napoleon used to date. |

There was a hiccup. Morner hadn't been acting entirely officially. He was just a lieutenant, not an ambassador. An ambassador had, in fact, been sent to Napoleon, asking him on his opinion on who should succeed Charles XIII. Napoleon had backed King Frederick VI of Denmark-Norway, hoping to unite Scandinavia under a friendly flag. When he found out that Jean Baptiste had been offered the position, he wasn't crazy about Bernadotte being on the Swedish throne, but he loved the idea of a Frenchman on the throne. He went to his ex-stepson, Eugene, the Viceroy of Italy, and offered the position to him. Eugene refused. Napoleon decided to, well, not support Bernadotte, because if Bernadotte failed it would be embarrassing for Napoleon, but he wasn't not not supporting Bernadote.

Jean Baptiste discussed it with his wife, and after getting Napoleon's 'do it if you want', formally submitted his name for consideration. Baron Morner was an enthusiastic hype-man, campaigning for Bernadotte much like how modern pundits campaign for elected officials. Though there was a significant faction in favor of Frederick VI, and King Charles still wanted to elect his idiot cousin, Jean Baptiste was elected unanimously.

|

| Some of today's Bernadotte's. Pictured: King Carl Gustav XVI, his daughter, Crown Princess Victoria, and her eldest child, Princess Estelle. |

The new Charles was good to his word, and any worries of a French takeover of Sweden were assuaged for good in 1813 when Charles and Swedish forces joined the sixth coalition to fight against Napoleon. Charles was Crown Prince for about eight years, from 1810 to 1818. During this time, he conquered Norway, and unified Sweden and Norway again. By the time he became King, he had thoroughly won over his new people.

Jean Baptiste Bernadotte's legacy lives on today in the ruling family of Sweden. The current king, Carl Gustav XVI is the great, great, great, great grandson of Jean Baptiste. When Carl Gustav's daughter, Crown Princess Victoria, becomes Queen Regnant, she will be the eighth Bernadotte monarch.

Bernadotte: Napoleon's Marshal, Sweden's King by Alan Palmer

Karl Johann XIV-King of Norway and Sweden

Charles XIV, King of Sweden and Norway

The Bernadotte Dynasty

The House of Bernadotte

Charles John XIV, King of Sweden and Norway