Taken from her home and family, thrust into a strange land, surrounded by strangers, Phillis Wheatley had an inauspicious start to life, yet became one of the most august women of her time. She was the first poet of African descent, and the second woman to be published in the United States. She was a genius, speaking three languages, and well versed in classical studies, science, and literature. Yet, she spent most of her life a slave, and died poor and alone at the young age of 31.

Phillis' exact date of birth is unknown, but it is generally accepted that she was seven years old when she was taken to America in 1761. She was captured by slavers somewhere on the west coast of Africa, likely in Senegal, Gambia, or Ghana, and boarded onto a schooner named The Phillis. The Phillis was captained by Peter Gwinn, who had been charged with bringing back a large human cargo of African males to be sold in the new world. Gwinn wasn't as successful as the ship's owner, Timothy Finch, had hoped, instead bringing back a small cargo of women and children, many of whom were very ill.

Phillis was one of those who were very ill. She was a refuse slave--or a slave who wouldn't fetch a very good price. She has been described as being 'slender, frail, having shed her two front teeth', and the slave seller wasn't confident that she was going to live long, let alone that he was going to get much money for her. When Mrs. Susanna Wheatley¹ offered ten pounds, the slave seller gratefully let Phillis go, happy to have gotten some return on his investment.

Susanna took Phillis home, and named her after the ship that had stolen her from her homeland. Despite the fact that the Wheatley's had several other slaves, Phillis was not placed among them. Out of some maternal whim, or twist of sympathy, Susanna gave Phillis her own room. When Phillis showed signs of perhaps being able to read and write, Susanna set her daughter Mary to tutoring the young Phillis, and within sixteen months Phillis was completely fluent and literate in English, able to 'read any, most difficult Parts of Sacred Writing to the great Astonishment of all who heard her'.²

Teaching a slave to read was completely unheard of at the time, and a master who gave their slaves education was something of a loose cannon, as educating slaves endangered the whole practice of slavery. Not content to be volatile rebels, the Wheatley's also had Phillis tutored in Greek, Latin, history, literature, astronomy, classics, and, of course, religion.

America at the time was in the middle of what is called the First Great Awakening. Religious revival was in the air, and being pious and well versed in the bible was in vogue. The Wheatley's, much like the rest of the people in the colonies, were swept up in the excitement. They were avid church goers, and they took Phillis to church with them. Because of this, Phillis grew up, and remained, a devout Protestant her entire life.

The Wheatley's treated Phillis like one of the family. She was, essentially, a second daughter. She wasn't expected to do housework or manual labor like the other slaves, she was taken to church with her masters, and allowed to eat and spend time with the family. When the Wheatley's went on social calls, they often took Phillis with them, including her in the conversation. She was treated with respect not only by the Wheatley's, but by their associates as well, and she impressed many of the most eminent men and women of Boston with her learning and precociousness.

However, don't be fooled. The Wheatley's still sucked butt. Despite treating Phillis as one of the family, they still owned her. She was still a slave, even if she wasn't forced to do menial labor. She wasn't free, but she didn't fit with the other slaves either. The Wheatley's forbade Phillis from socializing with the other slaves, isolating her, and stranding her in between worlds.

In 1767, when Phillis was thirteen, her first poem was published. Phillis had shown a great talent for writing, a talent the Wheatley's encouraged. When Phillis wrote a poem "On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin" in honor of two men drowned at sea, Susanna saw that it was published in the newspaper, The Newport Mercury. Several other poems followed, and Phillis' work began to gain recognition in the colonies and across the Atlantic.

Phillis' first really successful poem, “An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of the Celebrated Divine George Whitefield” was published in 1770, and it was about this time that Phillis, with Susanna's help, started putting together a collection of poetry for publication. It was titled Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, and contained 28 poems. It would be published in 1773 when Phillis was eighteen.

Getting a book published in the late eighteenth century was no small feat. Publishers required a guarantee that people would buy the book, and some required that authors assume some of the costs of printing themselves. In Phillis' case, a list of 300 people who would buy the book was required by the publisher. Susanna lobbied heavily, and while she was able to collect some signatures, some of them being of the most eminent and learned men in Boston, she was not able to collect the required 300. This was because there were not 300 people in Boston who believed that poetry could be written by a slave. Discouraged by the American market, Phillis and Susanna decided to take Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, across the pond, where the public had already been proven to be more receptive to African authors.

Publishing the book in England required jumping through several hoops. Firstly, the publisher, Archibald Bell, was skeptical of the books authorship, and wanted proof that the book was, in fact, written by a slave. To provide evidence, Susanna assembled a group of eighteen men willing to sign affidavits certifying Phillis' authorship. These were some of the most educated and important men in Boston³, many of whom were prominent political and religious figures. The quizzed Phillis on her work, and all signed a paper saying that Phillis was the author of the book.

Once the publisher had the affidavits, he required that Phillis have someone to dedicate her work to. The dedication, and dedicatee was very important. A book had to be dedicated to a public figure, who was, essentially, vouching to the public that the book was quality work. For Poems on Various Subjects, Phillis and the Wheatley's chose Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon.

The countess was chosen because Phillis had a tenuous connection to her. One of Phillis' first important poems, 'An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of that Celebrated Divine, and Eminent Servant of Jesus Christ, the Reverend and Learned George Whitefield' had been about George Whitefield, who had been the personal chaplain to the countess. The Wheatley's used this connection to forward Phillis' book to the countess, going as far as to have one of their ship captains read the entire work to the countess.

The countess was charmed, and she write to the publisher, allowing the work to be dedicated to her. With the dedication and affidavits in order, Phillis' book was cleared for publication, and came out in the summer of 1773.

Phillis' book was well received, circulating among the upper class, attracting astonishment that a slave could write so well. England, at the time, had a much more lax approach to racism, and while slavery wasn't yet illegal in the British isles, society was sympathetic to the plight of the enslaved. Phillis was received as an equal everywhere, and became a social star.

Unfortunately, Susanna Wheatley fell ill, and Phillis had to quickly leave London in September of 1773, depriving her of the chance to meet both the King and the Countess of Huntingdon. She returned to Boston, and was freed in October of that year. On March 3, 1774, Susanna Wheatley died.

With the death of Susanna, the Wheatley family disintegrated. The eldest son, Nathaniel, was living across the Atlantic with his English wife, and John Wheatley had fled Boston because of the British troops occupying the city after the events of the Boston Tea Party. Phillis, while she did have some money of her own, was in no position to live independently, so she moved in with Mary Lathrop nee Wheatley, the daughter who had taught her to read, and the pair relocated to Newport, Rhode Island along with Mary's husband.

Phillis lived fairly uneventfully in Providence, continuing to write and participate in religious activities. The most notable thing to happen in this period was her correspondence with George Washington in early 1776.

Though the Wheatley family at large were loyal to the British crown, Phillis seemed to have some enthusiasm for independence. She hoped that with independence from Britain would come independence for all the enslaved Africans. On October 26, 1775 she sent a poem to General George Washington which enthusiastically proclaimed that the Americans would defeat the British, and that it would usher in a new era of freedom and prosperity. In this poem she created the goddess Columbia--the goddess who would come to represent America, and would be memorialized in the Statue of Liberty.⁴

George Washington was very impressed with her poem, and responded to her in a letter praising her talents. He invited her to come visit him at his headquarters in Cambridge, however it is highly unlikely that they ever met, given that Phillis would have had to cross British lines to reach him.

Phillis and the Lathrops returned to Boston in 1776, and Phillis married John Peters, a freed African, on November 26, 1778. Peters was a shopkeeper with a bad reputation. Contemporary accounts paint him as a villain who abused Phillis, and squandered their money. They stopped living together about a year after their marriage. Nevertheless, they had two children, neither of whom lived more than a day.

In 1779 Phillis started lobbying to publish a second book of poetry. Due to the Revolutionary War she was unable to get in touch with her contacts back in England, and there wasn't much of a market for poetry in America at the time. Phillis had to take a series of janitorial jobs in boarding houses, and died in childbirth on December 5, 1784. No one attended her funeral.

Phillis faded into relative obscurity for about 50 years after her death. Her second book of poetry was finally released in 1834, and another was printed in 1864. She was often held up as an example of the humanity and capability of enslaved Africans by abolitionists of her age, and her work has strong, but subtle abolitionist themes. She is remembered today as being one of the best writers of early America, and as being the first published African American writer.

¹Or possibly Susanna's husband, John. Sources disagree.

²From a letter by her master John Wheatley. (sic) throughout.

³For those, said men were:

|

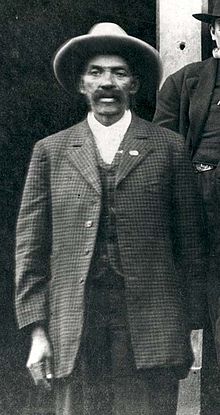

| This is the only contemporary portrait of Phillis |

Phillis was one of those who were very ill. She was a refuse slave--or a slave who wouldn't fetch a very good price. She has been described as being 'slender, frail, having shed her two front teeth', and the slave seller wasn't confident that she was going to live long, let alone that he was going to get much money for her. When Mrs. Susanna Wheatley¹ offered ten pounds, the slave seller gratefully let Phillis go, happy to have gotten some return on his investment.

Susanna took Phillis home, and named her after the ship that had stolen her from her homeland. Despite the fact that the Wheatley's had several other slaves, Phillis was not placed among them. Out of some maternal whim, or twist of sympathy, Susanna gave Phillis her own room. When Phillis showed signs of perhaps being able to read and write, Susanna set her daughter Mary to tutoring the young Phillis, and within sixteen months Phillis was completely fluent and literate in English, able to 'read any, most difficult Parts of Sacred Writing to the great Astonishment of all who heard her'.²

Teaching a slave to read was completely unheard of at the time, and a master who gave their slaves education was something of a loose cannon, as educating slaves endangered the whole practice of slavery. Not content to be volatile rebels, the Wheatley's also had Phillis tutored in Greek, Latin, history, literature, astronomy, classics, and, of course, religion.

America at the time was in the middle of what is called the First Great Awakening. Religious revival was in the air, and being pious and well versed in the bible was in vogue. The Wheatley's, much like the rest of the people in the colonies, were swept up in the excitement. They were avid church goers, and they took Phillis to church with them. Because of this, Phillis grew up, and remained, a devout Protestant her entire life.

The Wheatley's treated Phillis like one of the family. She was, essentially, a second daughter. She wasn't expected to do housework or manual labor like the other slaves, she was taken to church with her masters, and allowed to eat and spend time with the family. When the Wheatley's went on social calls, they often took Phillis with them, including her in the conversation. She was treated with respect not only by the Wheatley's, but by their associates as well, and she impressed many of the most eminent men and women of Boston with her learning and precociousness.

However, don't be fooled. The Wheatley's still sucked butt. Despite treating Phillis as one of the family, they still owned her. She was still a slave, even if she wasn't forced to do menial labor. She wasn't free, but she didn't fit with the other slaves either. The Wheatley's forbade Phillis from socializing with the other slaves, isolating her, and stranding her in between worlds.

| Phillis' book. |

Phillis' first really successful poem, “An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of the Celebrated Divine George Whitefield” was published in 1770, and it was about this time that Phillis, with Susanna's help, started putting together a collection of poetry for publication. It was titled Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, and contained 28 poems. It would be published in 1773 when Phillis was eighteen.

Getting a book published in the late eighteenth century was no small feat. Publishers required a guarantee that people would buy the book, and some required that authors assume some of the costs of printing themselves. In Phillis' case, a list of 300 people who would buy the book was required by the publisher. Susanna lobbied heavily, and while she was able to collect some signatures, some of them being of the most eminent and learned men in Boston, she was not able to collect the required 300. This was because there were not 300 people in Boston who believed that poetry could be written by a slave. Discouraged by the American market, Phillis and Susanna decided to take Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, across the pond, where the public had already been proven to be more receptive to African authors.

Publishing the book in England required jumping through several hoops. Firstly, the publisher, Archibald Bell, was skeptical of the books authorship, and wanted proof that the book was, in fact, written by a slave. To provide evidence, Susanna assembled a group of eighteen men willing to sign affidavits certifying Phillis' authorship. These were some of the most educated and important men in Boston³, many of whom were prominent political and religious figures. The quizzed Phillis on her work, and all signed a paper saying that Phillis was the author of the book.

Once the publisher had the affidavits, he required that Phillis have someone to dedicate her work to. The dedication, and dedicatee was very important. A book had to be dedicated to a public figure, who was, essentially, vouching to the public that the book was quality work. For Poems on Various Subjects, Phillis and the Wheatley's chose Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon.

The countess was chosen because Phillis had a tenuous connection to her. One of Phillis' first important poems, 'An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of that Celebrated Divine, and Eminent Servant of Jesus Christ, the Reverend and Learned George Whitefield' had been about George Whitefield, who had been the personal chaplain to the countess. The Wheatley's used this connection to forward Phillis' book to the countess, going as far as to have one of their ship captains read the entire work to the countess.

The countess was charmed, and she write to the publisher, allowing the work to be dedicated to her. With the dedication and affidavits in order, Phillis' book was cleared for publication, and came out in the summer of 1773.

|

| Statue of Phillis done by Edmonia Lewis |

Unfortunately, Susanna Wheatley fell ill, and Phillis had to quickly leave London in September of 1773, depriving her of the chance to meet both the King and the Countess of Huntingdon. She returned to Boston, and was freed in October of that year. On March 3, 1774, Susanna Wheatley died.

With the death of Susanna, the Wheatley family disintegrated. The eldest son, Nathaniel, was living across the Atlantic with his English wife, and John Wheatley had fled Boston because of the British troops occupying the city after the events of the Boston Tea Party. Phillis, while she did have some money of her own, was in no position to live independently, so she moved in with Mary Lathrop nee Wheatley, the daughter who had taught her to read, and the pair relocated to Newport, Rhode Island along with Mary's husband.

Phillis lived fairly uneventfully in Providence, continuing to write and participate in religious activities. The most notable thing to happen in this period was her correspondence with George Washington in early 1776.

Though the Wheatley family at large were loyal to the British crown, Phillis seemed to have some enthusiasm for independence. She hoped that with independence from Britain would come independence for all the enslaved Africans. On October 26, 1775 she sent a poem to General George Washington which enthusiastically proclaimed that the Americans would defeat the British, and that it would usher in a new era of freedom and prosperity. In this poem she created the goddess Columbia--the goddess who would come to represent America, and would be memorialized in the Statue of Liberty.⁴

George Washington was very impressed with her poem, and responded to her in a letter praising her talents. He invited her to come visit him at his headquarters in Cambridge, however it is highly unlikely that they ever met, given that Phillis would have had to cross British lines to reach him.

Phillis and the Lathrops returned to Boston in 1776, and Phillis married John Peters, a freed African, on November 26, 1778. Peters was a shopkeeper with a bad reputation. Contemporary accounts paint him as a villain who abused Phillis, and squandered their money. They stopped living together about a year after their marriage. Nevertheless, they had two children, neither of whom lived more than a day.

|

| Phillis' most famous poem |

Phillis faded into relative obscurity for about 50 years after her death. Her second book of poetry was finally released in 1834, and another was printed in 1864. She was often held up as an example of the humanity and capability of enslaved Africans by abolitionists of her age, and her work has strong, but subtle abolitionist themes. She is remembered today as being one of the best writers of early America, and as being the first published African American writer.

¹Or possibly Susanna's husband, John. Sources disagree.

²From a letter by her master John Wheatley. (sic) throughout.

³For those, said men were:

- Thomas Hutchinson, Governor of Virginia

- Andrew Oliver, Lieutenant Governor of Virginia

- Reverend Mather Byles

- Joseph Green, a poet and satirist

- Reverend Samuel Cooper, known as 'the silver tongued preacher'

- James Bowdoin, scientist and poet

- John Hancock

- Reverend Samuel Mather

- Thomas Hubbard

- Reverend Charles Chauncy

- John Moorhead

- John Erving

- James Pitts

- Harrison Gray

- Richard Carey

- Reverend Edward Pemberton

- Reverend Andrew Elliot

- John Wheatley, Phillis' master

⁴ She also compared George Washington to a god, and equated him with the concept of freedom.

Sources

The Trials of Phillis Wheatley by Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Phillis Wheatley: Biography of Genius in Bondage by Vincent Carretta

Complete Writings of Phillis Wheatley published by Penguin classics

"A Slave's Subtle War: Phillis Wheatley's Use of Biblical Myth and Symbol" by Sondra O'Neale

Phillis Wheatley-Poetry Foundation

Phillis Wheatley-The History Chicks

Phillis Wheatley-National Women's History Museum

Phillis Wheatley-Encyclopedia Britannica

Phillis Wheatley-Biography

Phillis Wheatley-National Portrait Gallery

Sources

The Trials of Phillis Wheatley by Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Phillis Wheatley: Biography of Genius in Bondage by Vincent Carretta

Complete Writings of Phillis Wheatley published by Penguin classics

"A Slave's Subtle War: Phillis Wheatley's Use of Biblical Myth and Symbol" by Sondra O'Neale

Phillis Wheatley-Poetry Foundation

Phillis Wheatley-The History Chicks

Phillis Wheatley-National Women's History Museum

Phillis Wheatley-Encyclopedia Britannica

Phillis Wheatley-Biography

Phillis Wheatley-National Portrait Gallery