Navarre from beginning to end wielded a significant amount of power, especially for its size and relative lack of natural resources. Caught between France and Spain, located in a strategic point in the Pyrenees mountains, it's no surprise that Navarre's powerful neighbors eventually gobbled it up, leaving the only remnants of Navarre in regional toponyms. However, in the seven centuries between its inception and it's ultimate absorption into larger kingdoms, Navarre managed to be one of the most progressive of the medieval kingdoms, practicing religious tolerance and allowing women to inherit the throne, making it one of the best places to be a woman or non-Christian in medieval Europe.

Navarre was blessed by location. A mountainous kingdom, it controlled the only pass through the Pyrenees Mountains between France and Spain. It controlled several pilgrim routes and served at various times in its history as a buffer state between Gascony/England/France and Castille/Aragon/Leon.¹ Because of this, alliances with Navarre were very attractive, especially given that Navarre wasn't the type to go quietly into the night.

Navarre began ethnically Basque. There's quite a bit of debate as to where the first Basques came from, but by the 700s when Navarre first started out as the Kingdom of Pamplona, the region was comprised of Basques, Moors, and Basque-Moors, the results of Basque-Moor intermarriage and conversion to Islam after the Basque kings agreed to subordination under the Caliphates. As French influence grew in the 1200s the human landscape of Navarre began to include more Francophonic characteristics. French became a co-language with Navarro-Aragonese (Occitan).

It is difficult to piece together the story of Navarre. Much of what we know about Navarre today comes from the stories of its rulers. Unlike other countries of the time, there isn't a good record about daily life for peasants or nobles. However, there are really good records of who Navarre fought, which was more or less everyone around them. To get even a general idea of Navarrese history, you have to go deep into the history of its royal families. Such depth would require a several hundred-page-long book, and we don't have that sort of time. So, to sum it up:

Navarre was wrested from the Cordoba Caliphate in 824 by Inigo Arista, founder of the House of Iniguez. Navarre was, initially, named "The Kingdom of Pamplona", and in fact didn't come to be known as Navarre until the mid-1100s. The Kingdom of Pamplona was, unsurprisingly, located around the now Spanish city of Pamplona and extended into modern French territory. Inigo and his two successors spent their lives fighting against the Cordoba Caliphate, who were the major power in the region. Though they were briefly forced into vassalage to the Cordobas, Navarre ultimately remained an independent kingdom.

The House of Jimenez oversaw Navarre's most successful military expansions, reaching its greatest size under the aptly named Alfonso the Battler. He gained control of most of Castile and Leon through marriage to Urraca of Leon. Unfortunately, he and Urraca couldn't stand each other, and he lost his new territories in the divorce.

Jimenez also oversaw Navarre's vassalage to the Holy See, usually known as the Vatican. Unlike it's vassalage to Cordoba, or later to Aragon and France, this was voluntary. For most of Navarre's existence as a country, it was a profoundly Catholic nation, participating in two crusades, and swearing fealty to at least three popes.

Despite this decidedly pro-Catholic stance, Jimenez Navarre, and Navarre for the rest of its inception, was remarkably protective of its Jews, welcoming in Jews that had been expelled from other countries, and allowing them to participate in their own governance.

Navarre passed into French control in 1234, and though it maintained nominal independence, it was, essentially, the red-headed stepchild of France, governed by a series of oppressive French governors. Still, this era saw the codification of law and the rise of a middle class. Two houses ruled during this era of French domination: the House of Blois² and the House of Capet. Several of the rulers of this era never even stepped foot in Navarre. Each of these houses produced one queen regnant--Joan I and Joan II.

With the death of Joan I, Navarre passed to her daughter Joan II, who straddled the House of Capet, and the House of Evreux. Joan II was queen regnant in her own right. Navarre has no adherent of Salic Law. However, her husband, Phillip, got his knickers in a twist. Having been denied the throne of France, he was irritated that his wife got to rule a country but he didn't. After extensive lobbying, both Joan and Philip were crowned as co-rulers.

This new House of Evreux oversaw some of the most turbulent and progressive times of Navarrese history. The monarchs after Joan II and Philip were the first in more than a century to actually have been born in Navarre. The Navarrese monarchs of the time had significant holdings in France, which saw expansion and deflation, depending on the day. Protections were put in place to protect Navarrese Muslims, and a Supreme Court was established.

Unfortunately, the death of Navarre's third Queen Regnant--Blanche I--in 1441 spelled the beginning of the end for Navarre. The throne was grabbed by Blanche's Aragonese Trastamara husband instead of her son, sparking a civil war that weakened the country. The House of Trastamara saw only two monarchs, and the succeeding House of Foix saw only two as well before Upper Navarre (Navarre on the Spanish side) was conquered by Aragon.

With only Lower Navarre (the French side) left, Navarre was ruled by the House of d'Albret, a two-ruler house that boasted Navarre's most impressive Queen Regnant--Jeanne III.

Jeanne was a Renaissance princess, and she was swept up in the Reformation. Like Henry VIII, she had her country converted to Protestantism (though with less bloodshed). She also threw her weight behind the French Huguenots, who were a constant thorn in the side of the Catholic French monarchs. Her constant warring with France, and the concessions she was forced into, saw Lower Navarre absorbed into France for good on her death.

The Middle Ages saw a large amount of small states rise and fall, especially on the turbulent Iberian Peninsula. Many of them are more or less forgotten today. We remember Navarre because of its longevity, its political power, and its progressive (for the time) stance on human rights.

Navarre lasted as an independent entity in some form from its inception in 824 until the absorption of Lower Navarre into France in 1620. It saw nine royal houses and 38 individual monarchs. Several periods of this time included vassalage to the Cordoba Caliphate, Aragon, France, or the Holy See. Despite this, Navarre maintained a separate identity, still remaining distinctly Navarrese.

Navarre's political power was backed both by impressive political skills and by a fearsome fighting force. Navarrese royalty intermarried with royals from Castile, Leon, Aragon, the Cordoba Caliphate, France, and England. Notorious fourteenth-century monarch, Charles the Bad, was especially wily, playing France and England off each other to expand his territory. Jeanne d'Albret, the last truly Navarrese ruler of Navarre, skillfully negotiated with Catherine de Medici to maintain Navarrese sovereignty and freedom of religion.

Words were backed up with a strong arm. From its very inception, Navarre had been a state with a strong military. In the years of the House of Iniguez and the House of Jimenez, it was constantly at war with the Muslim forces that occupied the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula or with its neighbor, Aragon. After its first vassalage to France, Navarre became a sort of mercenary farm, used by French-Navarrese monarchs to pad out their French army and to advance their interest militarily in the Iberian peninsula and the south of France. After the reign of Charles the Bad, the most notorious Navarrese warmonger, Navarrese mercenaries become popular all over the continent.

Navarre was an incredible country--progressive for a medieval state, incredibly powerful, and long-lived. While it has been more or less forgotten today, it left a large mark on history and was instrumental in making modern European nations what they are today.

¹It is worth mentioning that Spain and France as modern states did not exist for much of Navarre's history but were instead split up into a series of smaller states continually at war with each other.

²Or the house of champagne, depending on how you want to split things.

This article was edited by Mara Kellogg

Sources

Pamplona. Navarre. History of Early Christian Kingdoms

|

| Navarre, 1000 |

Navarre began ethnically Basque. There's quite a bit of debate as to where the first Basques came from, but by the 700s when Navarre first started out as the Kingdom of Pamplona, the region was comprised of Basques, Moors, and Basque-Moors, the results of Basque-Moor intermarriage and conversion to Islam after the Basque kings agreed to subordination under the Caliphates. As French influence grew in the 1200s the human landscape of Navarre began to include more Francophonic characteristics. French became a co-language with Navarro-Aragonese (Occitan).

It is difficult to piece together the story of Navarre. Much of what we know about Navarre today comes from the stories of its rulers. Unlike other countries of the time, there isn't a good record about daily life for peasants or nobles. However, there are really good records of who Navarre fought, which was more or less everyone around them. To get even a general idea of Navarrese history, you have to go deep into the history of its royal families. Such depth would require a several hundred-page-long book, and we don't have that sort of time. So, to sum it up:

|

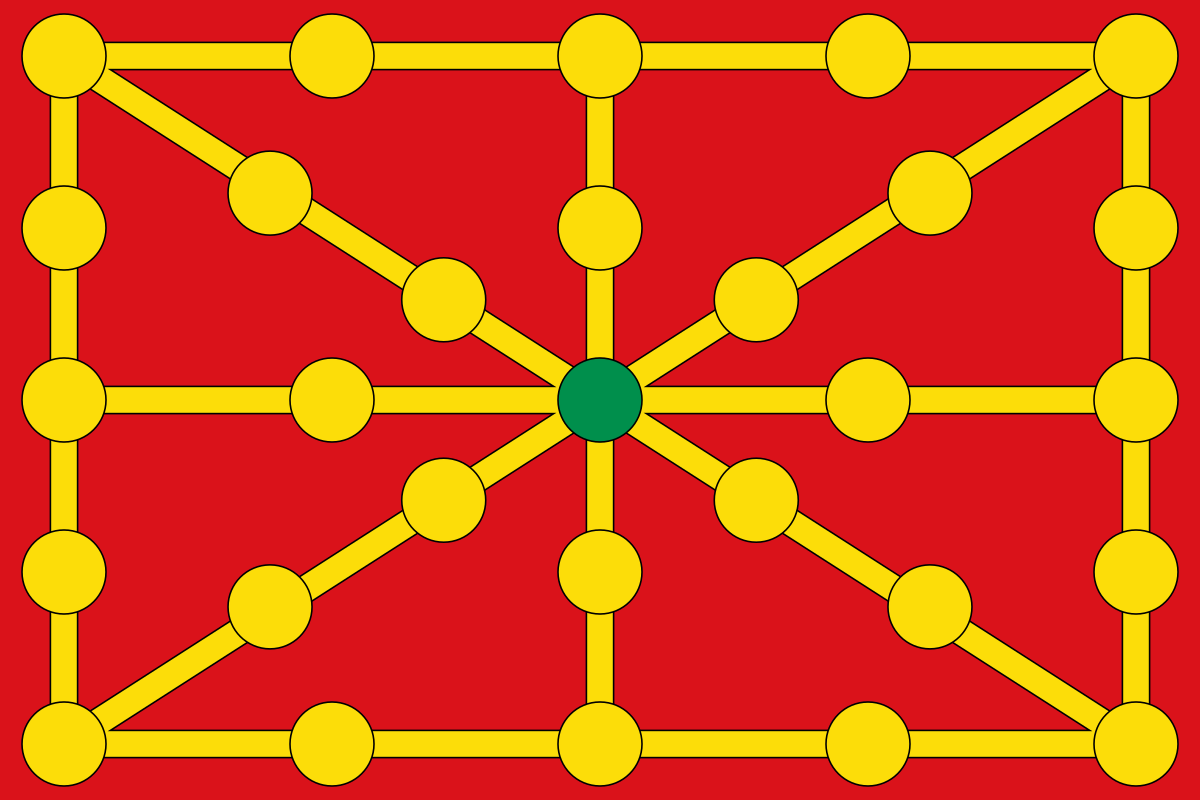

| Navarrese flag |

The House of Jimenez oversaw Navarre's most successful military expansions, reaching its greatest size under the aptly named Alfonso the Battler. He gained control of most of Castile and Leon through marriage to Urraca of Leon. Unfortunately, he and Urraca couldn't stand each other, and he lost his new territories in the divorce.

Jimenez also oversaw Navarre's vassalage to the Holy See, usually known as the Vatican. Unlike it's vassalage to Cordoba, or later to Aragon and France, this was voluntary. For most of Navarre's existence as a country, it was a profoundly Catholic nation, participating in two crusades, and swearing fealty to at least three popes.

|

| Alfonso the Battler and groupies |

Navarre passed into French control in 1234, and though it maintained nominal independence, it was, essentially, the red-headed stepchild of France, governed by a series of oppressive French governors. Still, this era saw the codification of law and the rise of a middle class. Two houses ruled during this era of French domination: the House of Blois² and the House of Capet. Several of the rulers of this era never even stepped foot in Navarre. Each of these houses produced one queen regnant--Joan I and Joan II.

With the death of Joan I, Navarre passed to her daughter Joan II, who straddled the House of Capet, and the House of Evreux. Joan II was queen regnant in her own right. Navarre has no adherent of Salic Law. However, her husband, Phillip, got his knickers in a twist. Having been denied the throne of France, he was irritated that his wife got to rule a country but he didn't. After extensive lobbying, both Joan and Philip were crowned as co-rulers.

This new House of Evreux oversaw some of the most turbulent and progressive times of Navarrese history. The monarchs after Joan II and Philip were the first in more than a century to actually have been born in Navarre. The Navarrese monarchs of the time had significant holdings in France, which saw expansion and deflation, depending on the day. Protections were put in place to protect Navarrese Muslims, and a Supreme Court was established.

|

| Jeanne III, also known as Jean d'Albret |

With only Lower Navarre (the French side) left, Navarre was ruled by the House of d'Albret, a two-ruler house that boasted Navarre's most impressive Queen Regnant--Jeanne III.

Jeanne was a Renaissance princess, and she was swept up in the Reformation. Like Henry VIII, she had her country converted to Protestantism (though with less bloodshed). She also threw her weight behind the French Huguenots, who were a constant thorn in the side of the Catholic French monarchs. Her constant warring with France, and the concessions she was forced into, saw Lower Navarre absorbed into France for good on her death.

The Middle Ages saw a large amount of small states rise and fall, especially on the turbulent Iberian Peninsula. Many of them are more or less forgotten today. We remember Navarre because of its longevity, its political power, and its progressive (for the time) stance on human rights.

Navarre lasted as an independent entity in some form from its inception in 824 until the absorption of Lower Navarre into France in 1620. It saw nine royal houses and 38 individual monarchs. Several periods of this time included vassalage to the Cordoba Caliphate, Aragon, France, or the Holy See. Despite this, Navarre maintained a separate identity, still remaining distinctly Navarrese.

| Navarrese royal crest |

Words were backed up with a strong arm. From its very inception, Navarre had been a state with a strong military. In the years of the House of Iniguez and the House of Jimenez, it was constantly at war with the Muslim forces that occupied the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula or with its neighbor, Aragon. After its first vassalage to France, Navarre became a sort of mercenary farm, used by French-Navarrese monarchs to pad out their French army and to advance their interest militarily in the Iberian peninsula and the south of France. After the reign of Charles the Bad, the most notorious Navarrese warmonger, Navarrese mercenaries become popular all over the continent.

Navarre was an incredible country--progressive for a medieval state, incredibly powerful, and long-lived. While it has been more or less forgotten today, it left a large mark on history and was instrumental in making modern European nations what they are today.

¹It is worth mentioning that Spain and France as modern states did not exist for much of Navarre's history but were instead split up into a series of smaller states continually at war with each other.

²Or the house of champagne, depending on how you want to split things.

This article was edited by Mara Kellogg

Pamplona. Navarre. History of Early Christian Kingdoms