The French and Indian War, also known as the Seven Years War, the Third Silesian War, the Pomeranian War, or "that one war that Mrs. Painter talked about for, like, two weeks before we finally got to the Revolution."¹ was the first truly global war. As far as wars go, the French and Indian War is little more than a footnote on American history. On the outside, it may look relatively unimportant, but the French and Indian War changed the political landscape of North America in a way that would be instrumental to the Revolution that would occur twenty years after. And while it's no War of the Oaken Bucket, the French and Indian War merits discussion.

Winston Churchill described The Seven Years' War as being the first world war, and he wasn't wrong. The Seven Years' War was fought across the world, in Europe, North America, Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean². In Europe, multiple nations were fighting to curb the influence of Frederick the Great of Prussia. In India, the French and English supported various Indian rebel states in attempt to gain more favorable trade situations. In Africa, they tussled over the gum arabic trade. In the Caribbean, they fought over the financially lucrative sugar colonies.

In mainland North America, France, Spain, and England were fighting for land. France claimed to own all of the land watered by the Mississippi River, as well as Quebec and New France. Spain claimed Florida. Britain, by far the greediest of the bunch, claimed that the borders of their colonies continued horizontally from the east coast of the continent to the west coast. The fact that they weren't sure that there even was a west coast was conveniently overlooked.

With these overlapping claims, it's inevitable that the French and English would collide, and collide they did³. Enterprising British settlers, hungry for land, kept moving west, most notably into the lush Upper Ohio River Valley. Meanwhile, the French had been warring with the Meskwaki tribe, and in order to preserve some semblance of a peace, they had rerouted their trade routes, building forts in what was considered English territories.

In this era, forts were vital to controlling the land and protecting the settlers on the land. Because there was no wide police force, all policing had to come from the soldiers in the fort. The fort was also a place for civilians to hide in case of attack, and it protected travelers on the road. Forts were tremendously important, and both the French and the English were very touchy about the other side building forts on their land.

Things kicked off in 1753 when the Virginia lieutenant governor, Robert Dinwiddie, sent an enterprising young nobody named George Washington to Fort Le Boeuf to tell the French to get the heck off the metaphorical English lawn. France had built a string of forts between Lake Erie and modern Pittsburgh, and the English were less than pleased. Washington carried out his duty, and the French politely declined his eviction notice. The niceties covered, Dinwiddie declared the French forts an act of aggression, and sent William Trent to build forts of their own, and George Washington to kick the French out of their forts.

Aggression declared, it was time to pick teams. Both the French and the English had been trading with the native tribes, and they realized that having the locals on their side was not only good for business, but it was also good for the war effort. The majority of Native Americans sided with the French, as they were the lesser of two evils. The French were less inclined to settle the land, and they bothered to learn native languages, and try to make friends. The British were increasingly encroaching on traditional hunting grounds, and they didn't seem inclined to stop. For many tribes, siding with the French seemed the best way to ensure their way of life.

However, just because one particular native nation teamed up with the French or the English didn't mean they were friends. In fact, tribes frequently fought with their European allies in between fighting the opposing side. Allying with the Europeans wasn't so much joining together to fight for a common cause as it was attempting to keep the white men too busy fighting each other to steal from tribes.

The most significant native ally to the British was the Iroquois League, or the Haudenosaunee. The Haudenosaunee were a powerful group in the region, and the British claimed them as subjects. This was particularly convenient for them, because the Haudenosaunee, as far as the British understood it, claimed a portion of land that the French were settling on, and this strengthened the English claims to the area.

It's summer of 1754, and George Washington is continuing in his efforts to run the French out of town. The French had defeated William Trent and burned his unfinished fort, building the much nicer Fort Duquesne (pronounced Du-cane) on its ashes. Meanwhile, Washington had defeated a small force of French in Pennsylvania and had captured the French leader, Joseph de Jumonville. Jumonville claimed that he and his men were on a peace mission to warn the English they were trespassing. Washington was, by all accounts, willing to negotiate and let Jumonville and his men go, when his Haudenosaunee ally,⁴ Tanaghrisson, killed Jumonville. Tanaghrisson notoriously hated the French, claiming that the French had boiled and eaten his father.

The French were none too pleased about the death of their commander, and George Washington high tailed it to Great Meadows, where he started building a fort appropriately named Fort Necessity. The French arrived at Fort Necessity on July 3rd and soundly beat the English, sending Washington and his men scurrying back to Virginia.

This led to a string of French victories, allowing them to take several English forts, and establish their own forts all along the Ohio river. They were able to do this partly because of their superior military power but also partly because they had support from Paris. London, on the other hand, didn't care about what was happening in the colonies, with King George II stating "Let the Americans fight the Americans." This ambivalence would continue until future Prime Minister, William Pitt, realized that the North American colonies were key to establishing British world dominance.

Meanwhile, up north in Nova Scotia, trouble was brewing. A group of French settlers called the Acadians had been farming the land since the 1600s, when Nova Scotia was still New France. The presence of these Francophone peoples made the British nervous, so nervous that in 1730, the Acadians had been forced to swear an oath of neutrality. However, things were heating up in Nova Scotia, and the British governor, Charles Lawrence, was getting nervous. The French had built an enormous fortress, Fort Louisbourg, on Cape Breton island, and they had built another fort, Fort Beausejour, on the Chignecto river. While storming Fort Beausejour in 1755, a small group of Acadian militiamen were captured, and Lawrence seized upon the incidence as a violation of the Acadians' oath of neutrality made twenty years earlier.

Lawrence gathered a group of Acadian leaders and tried to compel them to take an oath of allegiance to the British. The Acadians, unsurprisingly, refused. Though they had been mostly ignored by their French liege lords, they weren't too fond of the British, who coveted their lands. Lawrence took their refusal as an act of aggression and signed a deportation order. All Acadian lands and possessions were forfeit, and the Acadians were to leave Nova Scotia forthwith.

Not trusting the Acadians to go quietly, Lawrence sent his men to surround churches on Sunday mornings when the majority of the Catholic Acadians were attending mass. They captured the men, and sent the women and children running. The English destroyed dykes and fields, and loaded the Acadians onto ships headed to France, Britain, and the colonies of South Carolina, Georgia, and Pennsylvania. While many Acadians fled to the forests and fought back, they were unsuccessful. Approximately 10,000 Acadians were deported, and more than a tenth of them died. Acadians who landed in English colonies landed to a cool reception and were forced to wander in search of a new home. A number of these Acadians ended up in Louisiana, becoming the people who would become to be known as the Cajuns.

Meanwhile, back in London, parliament was finally taking the war seriously. They sent a significant force to the colonies to fight the French, and their newly minted navy to cut off French supplies and reinforcements. The British started winning in the Americas, aided by their fancy new guerilla warfare tactics learned from the Native Americans.

The French were starting to get desperate. The war had been dragging on for eight years, and the French government was going bankrupt. The British were slowly taking away both their trade on mainland North America and their sugar colonies, and they were getting tired of it. They turned to their friends, the Spanish. In an agreement that would be later known as the Family Compact⁵, the Spanish agreed that if the British had not withdrawn from North America by May 1, 1762, Spain would enter the war.

This was meant to pressure the British into withdrawing. Unfortunately, Spain wasn't very intimidating. The English declared war on Spain in January of 1762 and thoroughly defeated them, taking Cuba, the Philippines, and the French Caribbean islands.

After these defeats, the French were ready to throw in the towel. Spain, France, and Britain signed the Treaty of Paris on February 10, 1763. In this treaty, Britain got Florida, Canada, and everything east of the Mississippi river. France got everything west of the Mississippi, as well as their sugar colonies. Spain got Cuba and the Philippines.

As the dust settled, the people in the Americas, native and non, realized that they had been massively screwed over. The Native Americans had hoped that fighting with the French and British would ensure that settlers kept off their lands in the Ohio River Valley. Unfortunately, with the French driven out, the British were free to settle where they pleased. Native Lands were snapped up at an alarming pace, and it was becoming increasingly impossible to keep settlers at bay.

Additionally, the war had been enormously expensive for the British government, and they had to find some way to pay for it. What better way to pay for it than taxing their colonies? These taxes would infuriate the colonists and ignite the spark that started the American Revolution.

¹Thanks, Mrs. Painter!

²Okay, sure, the Caribbean is technically a part of North America, but it's easy to forget that.

³At this point in the war, Spain was keeping itself to itself. They didn't have a horse in the Upper Ohio River Valley race. They wouldn't enter the war until later.

⁴Tanaghrisson was, specifically Seneca, though he may have been born into a different tribe. He was a significant Haudenosaunee leader, known by Europeans as "half-king."

⁵The French and Spanish kings were cousins.

This article edited by Mara Kellogg. Infographic made by Devan Hurst.

Sources

Who Fought in the French and Indian War?

French and Indian War-Ohio History Central

French and Indian War-Encyclopedia Britannica

French and Indian War/Seven Years' War

Incidents Leading Up to the French and Indian War

French and Indian War-History

Acadian Expulsion (The Great Upheaval)

Acadian Deportation, Migration, and Resettlement

French and Indian War-US History

French and Indian War Forts

The Battle of Fort Necessity

French and Indian War-Michigan State University

|

| North America at the beginning of the French and Indian War |

In mainland North America, France, Spain, and England were fighting for land. France claimed to own all of the land watered by the Mississippi River, as well as Quebec and New France. Spain claimed Florida. Britain, by far the greediest of the bunch, claimed that the borders of their colonies continued horizontally from the east coast of the continent to the west coast. The fact that they weren't sure that there even was a west coast was conveniently overlooked.

With these overlapping claims, it's inevitable that the French and English would collide, and collide they did³. Enterprising British settlers, hungry for land, kept moving west, most notably into the lush Upper Ohio River Valley. Meanwhile, the French had been warring with the Meskwaki tribe, and in order to preserve some semblance of a peace, they had rerouted their trade routes, building forts in what was considered English territories.

In this era, forts were vital to controlling the land and protecting the settlers on the land. Because there was no wide police force, all policing had to come from the soldiers in the fort. The fort was also a place for civilians to hide in case of attack, and it protected travelers on the road. Forts were tremendously important, and both the French and the English were very touchy about the other side building forts on their land.

|

| Drawing of Fort Le Boeuf |

Aggression declared, it was time to pick teams. Both the French and the English had been trading with the native tribes, and they realized that having the locals on their side was not only good for business, but it was also good for the war effort. The majority of Native Americans sided with the French, as they were the lesser of two evils. The French were less inclined to settle the land, and they bothered to learn native languages, and try to make friends. The British were increasingly encroaching on traditional hunting grounds, and they didn't seem inclined to stop. For many tribes, siding with the French seemed the best way to ensure their way of life.

|

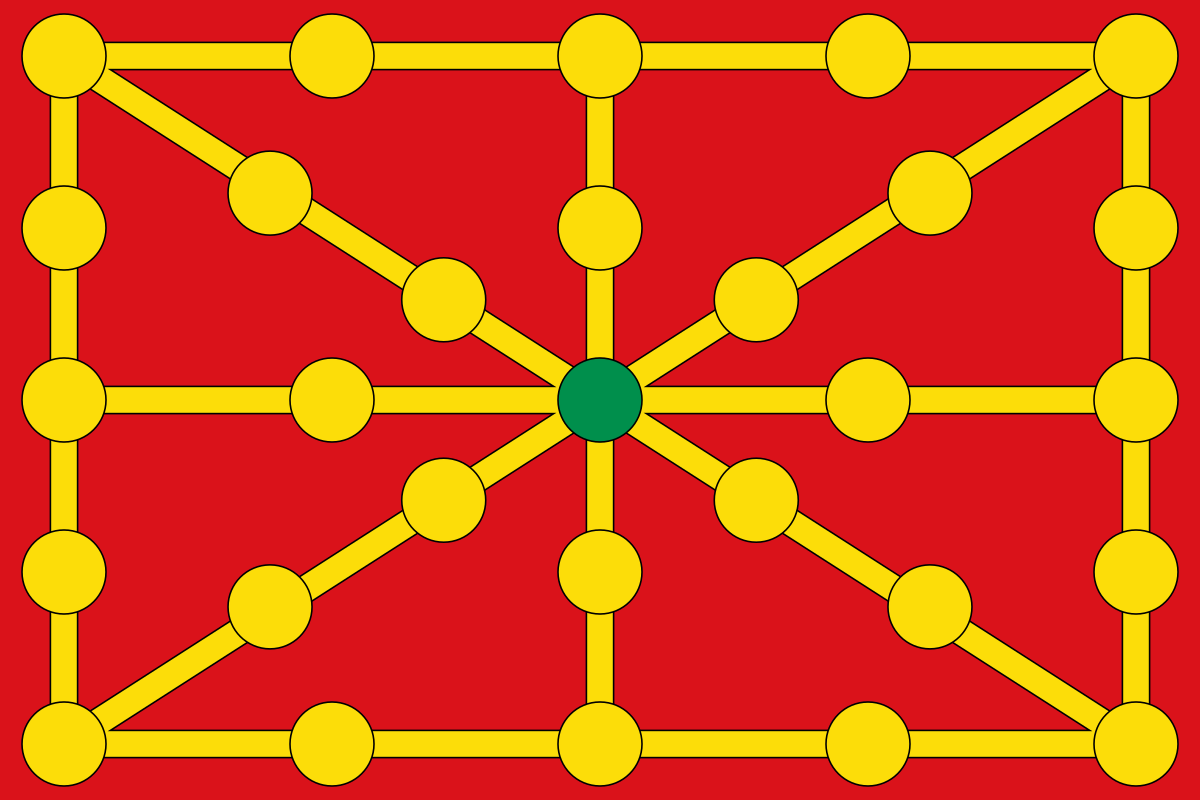

| Credit: Devan Hurst |

The most significant native ally to the British was the Iroquois League, or the Haudenosaunee. The Haudenosaunee were a powerful group in the region, and the British claimed them as subjects. This was particularly convenient for them, because the Haudenosaunee, as far as the British understood it, claimed a portion of land that the French were settling on, and this strengthened the English claims to the area.

It's summer of 1754, and George Washington is continuing in his efforts to run the French out of town. The French had defeated William Trent and burned his unfinished fort, building the much nicer Fort Duquesne (pronounced Du-cane) on its ashes. Meanwhile, Washington had defeated a small force of French in Pennsylvania and had captured the French leader, Joseph de Jumonville. Jumonville claimed that he and his men were on a peace mission to warn the English they were trespassing. Washington was, by all accounts, willing to negotiate and let Jumonville and his men go, when his Haudenosaunee ally,⁴ Tanaghrisson, killed Jumonville. Tanaghrisson notoriously hated the French, claiming that the French had boiled and eaten his father.

|

| Recreation of Fort Necessity |

This led to a string of French victories, allowing them to take several English forts, and establish their own forts all along the Ohio river. They were able to do this partly because of their superior military power but also partly because they had support from Paris. London, on the other hand, didn't care about what was happening in the colonies, with King George II stating "Let the Americans fight the Americans." This ambivalence would continue until future Prime Minister, William Pitt, realized that the North American colonies were key to establishing British world dominance.

Meanwhile, up north in Nova Scotia, trouble was brewing. A group of French settlers called the Acadians had been farming the land since the 1600s, when Nova Scotia was still New France. The presence of these Francophone peoples made the British nervous, so nervous that in 1730, the Acadians had been forced to swear an oath of neutrality. However, things were heating up in Nova Scotia, and the British governor, Charles Lawrence, was getting nervous. The French had built an enormous fortress, Fort Louisbourg, on Cape Breton island, and they had built another fort, Fort Beausejour, on the Chignecto river. While storming Fort Beausejour in 1755, a small group of Acadian militiamen were captured, and Lawrence seized upon the incidence as a violation of the Acadians' oath of neutrality made twenty years earlier.

Lawrence gathered a group of Acadian leaders and tried to compel them to take an oath of allegiance to the British. The Acadians, unsurprisingly, refused. Though they had been mostly ignored by their French liege lords, they weren't too fond of the British, who coveted their lands. Lawrence took their refusal as an act of aggression and signed a deportation order. All Acadian lands and possessions were forfeit, and the Acadians were to leave Nova Scotia forthwith.

|

| Depiction of the Acadians by artist Claude Picard |

Meanwhile, back in London, parliament was finally taking the war seriously. They sent a significant force to the colonies to fight the French, and their newly minted navy to cut off French supplies and reinforcements. The British started winning in the Americas, aided by their fancy new guerilla warfare tactics learned from the Native Americans.

The French were starting to get desperate. The war had been dragging on for eight years, and the French government was going bankrupt. The British were slowly taking away both their trade on mainland North America and their sugar colonies, and they were getting tired of it. They turned to their friends, the Spanish. In an agreement that would be later known as the Family Compact⁵, the Spanish agreed that if the British had not withdrawn from North America by May 1, 1762, Spain would enter the war.

|

| Map of North America at the end of the French and Indian War |

After these defeats, the French were ready to throw in the towel. Spain, France, and Britain signed the Treaty of Paris on February 10, 1763. In this treaty, Britain got Florida, Canada, and everything east of the Mississippi river. France got everything west of the Mississippi, as well as their sugar colonies. Spain got Cuba and the Philippines.

As the dust settled, the people in the Americas, native and non, realized that they had been massively screwed over. The Native Americans had hoped that fighting with the French and British would ensure that settlers kept off their lands in the Ohio River Valley. Unfortunately, with the French driven out, the British were free to settle where they pleased. Native Lands were snapped up at an alarming pace, and it was becoming increasingly impossible to keep settlers at bay.

Additionally, the war had been enormously expensive for the British government, and they had to find some way to pay for it. What better way to pay for it than taxing their colonies? These taxes would infuriate the colonists and ignite the spark that started the American Revolution.

¹Thanks, Mrs. Painter!

²Okay, sure, the Caribbean is technically a part of North America, but it's easy to forget that.

³At this point in the war, Spain was keeping itself to itself. They didn't have a horse in the Upper Ohio River Valley race. They wouldn't enter the war until later.

⁴Tanaghrisson was, specifically Seneca, though he may have been born into a different tribe. He was a significant Haudenosaunee leader, known by Europeans as "half-king."

⁵The French and Spanish kings were cousins.

This article edited by Mara Kellogg. Infographic made by Devan Hurst.

Who Fought in the French and Indian War?

French and Indian War-Ohio History Central

French and Indian War-Encyclopedia Britannica

French and Indian War/Seven Years' War

Incidents Leading Up to the French and Indian War

French and Indian War-History

Acadian Expulsion (The Great Upheaval)

Acadian Deportation, Migration, and Resettlement

French and Indian War-US History

French and Indian War Forts

The Battle of Fort Necessity

French and Indian War-Michigan State University