Either the twelfth or the twentieth wife of Mughal Emperor Jahangir, Nur Jahan was thrust into a life of fear and uncertainty. She was born while her parents were fleeing Persia, and was left on the road. Luckily, she was returned to her family, and was regarded as a lucky symbol from then after. Indeed, Nur Jahan was lucky for her family, because she would later become the Emperor Jahangir's favorite wife, and would, essentially, rule India in his stead, raising her family to the higher echelons of power with her.

|

| Contemporary portrait of Nur Jahan |

Born Mehrunnisa, Nur Jahan was the child of Mirza Ghiyas Beg and Asmat Begum, both high ranking members of the Persian court. Although it is unknown precisely why Mirza and Asmat had to flee Persia, it is known that they were fleeing to the court of Emperor Akbar (Jahangir's father) in search of a better life. Asmat was heavily pregnant, and gave birth along the road. Shortly after Nur Jahan was born, their caravan was attacked by robbers, leaving the family with little goods or money to start over in their new life. Fearing that they would be unable to provide for their daughter, her parents abandoned Mehrunnisa on the road.

According to legend, Mehrunnisa's mother was so distraught at having left her daughter behind, Mirza agreed to go back for the infant. When Mirza found Mehrunnisa underneath the tree they'd left her, a large cobra was looming over her, ready to swallow her whole. Mirza rushed at the snake, shouting, and the snake slunk off to do it's snakely business elsewhere. Mirza took his daughter back to his wife, and after telling the tale of his daughter's miraculous escape, their fellow travelers gave them the money to continue with their journey.

Other accounts say that Nur Jahan was left on the road, but was returned to her parents by other members of their caravan. Either way, shortly after the return of their daughter Mirza and Asmat arrived at Akbar's court, and settled into life as a mid-level bureaucrat.

|

Prince Selim, later the Emperor Jahangir

-World Grabber |

Mehrunnisa, who's name means 'The Sun of Women', grew up to become a beauty with an excellent education. She was an accomplished musician, poet, dancer, and artist, and she was also known for being witty and charming. She was also a fashionista, cook, and landscape artist. It is unsurprising that around 1594 she enchanted Prince Selim (later Jahangir) to the point that "he could hardly be restrained, by the rules of decency, to his place."

Prince Selim, heir to the throne, was so besotted with Mehrunnisa that he sought her hand in marriage. However, Mehrunnisa was already betrothed, and Emperor Akbar refused to break the engagement in favor of his son. So, at the age of 17, Mehrunnisa was married to Sher Afghan, a Persian courtier and adventurer. Her first marriage, while not a love match (or particularly propitious), gave Mehrunnisa

Ladili Begum, Mehrunnisa's only child.

Sher Afghan wasn't destined to live to a ripe old age. He died in 1607, after 13 years of marriage. There are many rumors saying that Selim, angered by Sher Afghan's refusal to break his betrothal, and lust for Mehrunnisa, had Sher Afghan killed.

The History of Hindostan, a somewhat sketchy contemporary source, gives an account of Selim's many failed attempts to have Sher Afghan killed, culminating in Selim ordering a small army to attack Sher Afghan. While if Selim actually arranged Sher Afghan's death is in doubt, it's proven fact that in 1607 Mehrunnisa was widowed at age 30.

|

| Ladili Begum |

Shortly after her husband's death, Mehrunnisa was summoned to Delhi to act as a lady-in-waiting to Prince Selim, now

Emperor Jahangir's stepmother. In 1611 Mehrunnisa was married again, this time to the Emperor, becoming his 12th (or 20th, sources disagree) wife.

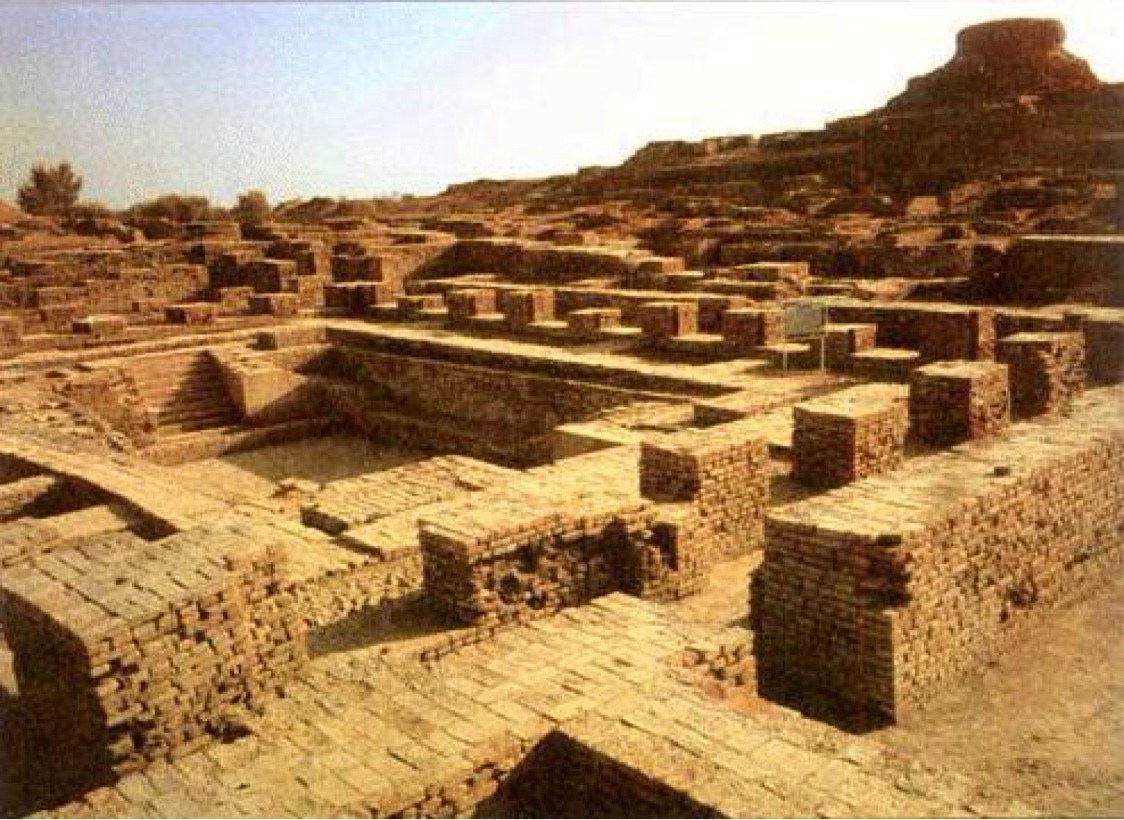

Emperor Akbar, Jahangir's father, had been a brilliant Emperor. Starting with only a small part of what is today Pakistan, Akbar managed to conquer all of north India, swallowing modern Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and parts of Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and China. He'd been a strict Sunni Muslim, but had encouraged religious discourse between Muslims, Hindus, Parsis, and Christians. He'd managed to woo local leaders of all religious persuasions to his side, yet retained his own religious supremacy (while building up a cult around himself).

Jahangir was a pale imitation of the brilliance of his father. Jahangir tried, undoubtedly; he extended his empire further down the Indian subcontinent, and managed to keep the empire more or less together. However, where Akbar had been focused on reform and expansion, Jahangir was focused on art and culture. Where Akbar had strictly followed the tenants of Islam (which forbid drugs and alcohol), Jahangir saw them more as guidelines, and at the time of his marriage to Mehrunnisa, was well on his way to becoming a non-functioning addict.

|

| Mughal Empire |

As far as marriages went, Jahangir and Mehrunnisa, renamed Nur Jahan (meaning 'Light of the World), were pretty happy. Jahangir was smitten with Nur Jahan, and she seemed to have returned his affection. While the couple never had children, Nur Jahan became Jahangir's Empress, and she was, by all accounts, a loving step mother. Jahangir and Nur Jahan had a great deal in common--they both loved the arts, and were passionate about hunting. Most importantly, Nur Jahan was more than willing to take over running the country, leaving Jahangir to lose himself in opium and mindless pleasure to his heart's content.

As the

de facto ruler of India, Nur Jahan put herself in the forefront of government work. She signed her name to royal decrees, along with her husband's, essentially giving herself the power to issue decrees, as well as promote and dismiss officials within the empire. She struck coinage in her own name, something that had never happened in Mughal history. She presided at Court, hearing cases about disputes between nobles, and passing judgement. She conducted international relations with other powerful women in foreign countries, and cemented trade deals. She was a shrewd businesswoman, and under her guidance India enjoyed an era of peace and prosperity.

|

| Nur Jahan |

Nur Jahan was also a philanthropist. She was particularly concerned with the women of her empire. Concerned that poor women would be unable to marry, she personally provided a dowry for over 500 women. She was the patroness of dozens of female poets and artists, many of whom's works survive today.

Despite her peaceful reputation, Nur Jahan had no scruples about warfare. She was an excellent sharpshooter herself, known as 'Tiger Slayer' for her remarkable feat of killing four tigers with six bullets. (keep in mind, these are 17th century bullets.) She planned and led several expansionist campaigns herself. When her husband was captured, she rescued him with a contingent of soldiers, riding in on an elephant, and successfully winning the battle despite the fact that both her and her elephant were injured.

Though the empire was prospering, Nur Jahan reigning after the death of her husband was out of the question. It was widely assumed that

Khurram (later Shah Jahan), Jahangir's third son, or Shahryar, Jahangir's youngest son. Nur Jahan initially supported Khurram, even marrying her niece Mumtaz Mahal to him. However, Khurram's hunger for power as he grew older led to Nur Jahan throwing her support behind Shahryar (who was married to her daughter Ladili).

When Khurram, now Shah Jahan, took power in 1628 he had Nur Jahan sent into exile in Lahore along with Ladili Begum, who was widowed after the death of Shahryar. Nur Jahan lived for another 18 years. Though she had backed his rival, Shah Jahan, kept her in comfort, and Nur Jahan was allowed to continue her building and artistic projects. She was kept from the political workings of the empire, but put her efforts into charity work instead, building mosques and assisting the poor. She died quietly in 1645.

|

| Silver rupees with Nur Jahan's name on them |

After her death, Shah Jahan did his best to erase Nur Jahan from history, having the coins with her name rescinded, and erasing her from official records. However, Shah Jahan was not at all successful--a testament to Nur Jahan's incredible influence. The hundreds of mosques and gardens she had constructed, as well as the waystation system for travelers she had established could not be demolished. Her artistic influence continues to influence India to this day. She invented several dishes which are now a staple of Indian cuisine, and the flowering patterned muslin she favored is a favorite in Indian fashion. Her style of stitched clothing and structured

saris is still the norm for Indian dress. A wealth of poetry written by her still survives, as do many of her buildings and gardens.

Nur Jahan was an extraordinary woman for any era, but especially for the era into which she was born. She ran an empire so skillfully that even her staunchest enemies grudgingly admitted that she was, what would later become her most famous epithet, 'A Woman Worthy to Be Queen'.

Sources

A History of Hindostan: Translated from the Persian: to Which are Prefixed Two Dissertations, the First Concerning the Hindoos, and the Second on the Nature of Despotism in Indian. Volume III by Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah Astarabadi Firishtah

Indian-Jahangir

Nur Jahan

Nur Jahan: Mughal Empress

Empress of Mughal Indian: Nur Jahan

World Changing Women: Nur Jahan