The mysterious Sappho of Lesbos is one of the most influential poets in history. Her poems--what she called her "Immortal Daughters-- not only influenced the poets of her day but inspired the Romantic and Victorian writers of the nineteenth century. Plato so respected her that he called her "the Tenth Muse," putting her on par with the nine daughters of Zeus.

Sappho was born sometime between 610 and 620 BCE on the island of Lesbos. She was from the town of Mytilene, or the town of Eresus, where her parents were well-established and respected aristocrats. There is evidence that her father was from Anatolia, which would have made Sappho not entirely Greek.

The theory of Sappho's family being migrants comes from the name of her father, and the spelling of Sappho's name. Her father was named Scamandronymus¹, a name familiar to readers of the Iliad. In the Iliad, the hero Achilles fights the Scamander, the god of the river that surrounded Troy. The name Scamandronymus comes from that minor god. Greeks were not in the habit of naming their children after the gods of rival, defeated kingdoms. And while every generation and nationality has parents who enjoy giving their children "unique" names, it is reasonable to assume that Sappho's father may have come from farther afield. To further support this theory, the spelling of Sappho's name varies, also appearing as Psappha, which has Anatolian origins.

Sappho had three brothers: Larichus, Erigyius, and Kharaxos. Not much is known about Erigyiu--not even his name is certain. Larichus was a handsome and successful young man who served as a cupbearer to a noble family. Kharaxos was, by far, the most colorful of the three. Sappho disapproved of him, as he had fallen in love with Rhodips,² an Egyptian courtesan. They were deeply in love, and if that wasn't disreputable enough, Kharaxos had to turn to piracy to support his passion for the beautiful Rhodips.

Now, it must be noted that the Kharaxos story comes from Ovid, a Roman writer who lived hundreds of years after Sappho. Ovid wrote quite a bit about Sappho, but he was, to put it delicately, full of crap. Any story about Sappho put forward by Ovid should be taken with a large grain of salt. However, in the "Brothers Poem" discovered in 2014, Sappho wrote:

Now, it must be remembered that Greek lyric poetry, the genre in which Sappho wrote, was highly personal and often autobiographical. It was a significant departure from the epic poetry of the previous centuries. Much like the later shift from the medieval art style to the Renaissance style, poetry went from epics, which were only concerned with the doings of gods and heroes, to lyrical poetry, which were interested in the individual. Sappho doesn't explicitly spell out that her brother was a pirate with a taste for Egyptian prostitutes; she tells us that he was a seafaring man of trade. The scurrilous details (true or not) come from Ovid.

In 604 BCE, Sappho and her family were exiled to the island of Sicily for non-specific political reasons. Sappho's parents were aristocrats with some political clout, and it is speculated that they may have made enemies with the wrong people. They settled in the city of Syracuse. There's no real record of what happened in Syracuse, but the city was later so proud of being the temporary home of Sappho that they later erected a statue of her and minted coins with her face on them.

While Sappho's remaining poetry isn't explicitly political, that Sappho may have written about politics isn't out of the question because so much of Sappho's poetry is lost. In her later life Sappho was a well-respected political figure; when she started talking politics isn't known, but it isn't out of the question that it was pre-exile. It's difficult to say because Sappho was somewhere between six and sixteen at the time of her family's exile.

Sappho's family returned to Lesbos some time in the 590s, and it was then when Sappho married Cercylas of Andros and had one daughter, Cleis, named after Sappho's mother.

Now, Sappho is synonymous with female homosexuality. The term "lesbian" takes its name from Sappho's home island of Lesbos, and the world "sapphic," a word used to describe female homosexuals of all stripes, takes its name from Sappho herself. While many historians and writers have tried to dismiss Sappho's more homoerotic poetry as "just gals being pals," only people reading Sappho in a state of willful ignorance would agree. In her poem "Gongyla," Sappho writes:

In Mnasidica, Sappho writes:

While the above more than demonstrates Sappho's love for women, her sexuality is not definite. While she has become the poster girl for lesbianism, it is just as likely that Sappho was what we now classify as bi or pansexual. There are many men mentioned in the long list of Sappho's lovers, and she did have a daughter. And, don't forget, there was her husband, Cercylas of Andros.

However, "Cercylas of Andros" may be some ancient writer's idea of a joke, as the name of Sappho's husband roughly translates to "Prick of the Isle of Man." It is possible that Cercylas was fictional, an addition from later writers to sanitize Sappho, or, as was popular with later Greek writers, to make fun of her. It is certain that Cleis existed, as Sappho wrote of her:

Sappho had a lot of friends, that much is certain. However, her relationship with them is just as murky and uncertain as the woman herself. Were they friends? Were they students? The true answer is lost to history. Tradition holds that Sappho ran a thiasos, a sort of finishing school for young ladies. Modern theories posit that she was more the hostess of an Ancient Greek salon, or a hetairia.

The idea that Sappho held a thaisos comes from the multiple young women she wrote poetry to as her students. Legend holds that her thiasos started out as a type of finishing school, where nobles would send their young daughters to be taught the womanly accomplishments they would need for marriage. However, over time Sappho's school evolved into a cult of Aphrodite and Eros, with Sappho as high priestess.

This theory is supported by the large volume of remaining poetry devoted to Aphrodite. And while there is no definitive proof of Sappho entering the priestesshood, she seems to have exercised an extreme level of devotion to the goddess of love and beauty. The only intact poem of Sappho's is her "Hymn to Aphrodite," and it ends with the provocative:

While Sappho may have thought herself to have a connection to Aphrodite, the amount of poetry dedicated to the goddess may exist because Sappho's bread and butter were wedding songs. (As a lyric poet, Sappho's poems were meant to be sung.) Ancient Greek weddings went on for several days, and singing was a major part of the celebrations. Songs comparing the groom to the great heroes of Greek lore, and the bride to the goddess Aphrodite or the infamous Helen were as much a staple of ancient weddings as Mendelssohn's Wedding March or Pachelbel's Canon are of modern weddings. In fragment 27, Sappho wrote:

It is possible that Aphrodite was just another love and beauty-centric subject for Sappho to write about and that Sappho held the goddess in no regard at all. It doesn't seem likely, but it's also possible that Sappho had purple hair and seven toes. With Sappho, most things are possible.

The idea that Sappho ran a hetairia comes from historians in the 20th and 21st centuries. Instead of running a school, it is believed that Sappho hosted a salon, exchanging artistic ideas with a diverse group of female poets and musicians. Even in this scenario, historical tradition portrays Sappho as being older than the rest of her gal pals and being in a mentoring position. While Sappho almost certainly did some instruction to the women performing her work, like any modern conductor would, there is no definitive proof that Sappho served as a teacher at all. In fact, Sappho's poetry suggests that she was more the member of an informal circle of friends. In a prelude, Sappho wrote:

Since history has, until recently, been looked at from an exclusively masculine point of view (stay with me, gentlemen), historical women have been relegated to rigid roles, no matter the fact that women, just like men, are complex and cannot fit into a single defined category. It is easy to put Sappho in a teacher/mother category because of her poetry about her daughter. Her work, in certain lights--especially her work dedicated to her friends--might come off as instructional. However, looked at in a different light, her poems read more like a woman giving her best friend advice. For example, in fragment 75 she says:

Then there's Fragment 33, which says:

Some of Sappho's poetry comes across as downright gossipy. Fragment 73 says:

Looking no farther than her poetry, it is clear that Sappho had a much more intimate relationship with her friends than that of a typical teacher. Sappho felt comfortable advising her friends. She clearly viewed them as equals and had no problem calling them out on their bullshit.

Sappho was often likened to Socrates, a noted pederast. Because of Sappho's equation with Socrates, and because historically society has had difficulty wrapping its collective heads around women and copulation, her sexuality was understood not from a female perspective but from a masculine perspective, and Ancient Greek male sexual norms were ascribed to her for centuries. It is only in recent years that Sappho's sexuality has been looked at from a female perspective.

The assumption of female homosexuality being exactly like male homosexuality brings in the interesting question of pederasty. Among Ancient Greek men, homosexuality was normalized within a pederastic context. An older nobleman found a hot piece of ass he wanted to "mentor," and the pair struck up a relationship. It was assumed that the same would apply to women. However, in no context does Sappho demonstrate a romantic and sexual love for a younger person. In fact, she makes her feelings on the matter quite explicit in fragment 72, saying:

Furthermore, when Sappho does describe a "maiden" in a sexual way, it's a maiden with another maiden, not with Sappho herself. In her poem "Telesippa," Sappho writes:

Whatever the dynamic of Sappho's friend group, Sappho garnered fame throughout the ancient world and not for her "school." She was referred to as "the poetess," an allusion to Homer, who was frequently called "the poet." This epitaph demonstrates that, in her own time, Sappho was though to be on par with Homer, who continues to remain the most influential male poet of antiquity.

Much of Sappho's poetry was set in what we now call "Sapphic meter," which consists of four lines--three long, the last short. The combination of stressed and unstressed syllables⁴ gives Sappho's poetry a distinct character that has been copied over and over again since she conceived it.

In addition to revolutionizing poetry, Sappho also made her mark on music. Sappho was a talented musician and vocalist herself and was noted for performing and leading performances of her own work. Based on her success, it is not unreasonable to assume that she must have been a good conductor as well. She was credited by her contemporaries with the invention of the pectis, a triangular harp, the plectrum, a type of proto-guitar pick, and the Mixolydian mode, a proto-scale that would survive into medieval music and make a comeback in modern popular music⁵.

There are two theories put out about the end of Sappho's life--the plausible and the dramatique. The plausible theory is that she died of old age in the 550s. The more theatrical story, put about by our old buddy Ovid⁶, is that, distraught over her unrequited love for a man named Phaon. This incident is referred to as the "Lucadian Leap," and appears multiple times in Greek mythology.

The connection of Sappho with the Lucadian Leap may have been an attempt at humor. It could be that this story of Sappho, a known homosexual, throwing herself from a cliff for love of a man could have been an attempt to satirize romantic love. Or an attempt to make fun of Sappho and her overblown love of love. Or, it's possible that when talking about the Lucadian leap, later writers weren't even talking about the Poetess Sappho of Lesbos, but instead another Sappho who was a courtesan working on Lesbos⁷.

Sappho was well respected during her lifetime. As mentioned, she was placed on the same level as Homer. Several of her turns of phrase entered Ancient Greek as common expressions. Phrases like "love, that sweet loosener of limbs," "I am of two minds," and "more golden than gold" entered the vernacular.

The philosophers Plato and Solon were big fans of hers. Solon, who wasn't known for his displays of emotions, reportedly:

While Sappho's work was largely passed around orally, her complete works were also gathered into a nine-volume book by the scholars at the Library of Alexandria in the 200s. The books were most likely organized by meter, and each contained somewhere around 1,300 lines of poetry. Unfortunately, these books no longer exist in their original form.

A lot of the myths swirling around Sappho come from stories put around by New Comedy writers after her death. Her sexual habits were exaggerated and mocked. She was dismissed as a licentious deviant. This led to her work being banned by Roman censors and burned by Pope Gregory VII.

Much of Sappho's work is lost, not just because of censors and the tragic loss of the Library of Alexandria, but because Aeolic, the dialect of Greek Sappho wrote in, is incredibly difficult to translate. Even a few centuries after her death Sappho was a hard read, so her works weren't constantly transcribed like the works of other writers. However, archaeologists are still digging up new Sapphic fragments. Her poetry has been found in the wrappings of Egyptian mummies, and occasionally turns up in the collections of private individuals. With any luck, new Sappho poems will keep turning up, and our knowledge of this pioneering poetess will continue to grow.

In fragment 30, she predicted:

¹Or Scamander, Simon, Eunomius, Eumenus, Eerigyus, Erigyius, Ecrytus, Semus, Camon, or Etarchus. Sources disagree, but Scamandronymus is the most common.

²Rhodopis is also sometimes known as Doricha.

³Artistic license has been taken with the statistic, but, despite not being based in actual fact, 99% probably isn't too far off.

⁴For a much better, and painfully exact description of what Sapphic Meter is, click the hyperlink.

⁵For more information about modes, go here for a comprehensive explanation.

⁶This theory may have also originated from the Greek dramatist Menander, or the Roman writer Lucian.

⁷However, the existence of other Sappho is also disputed. She is often used to explain later stories of Sappho the Poetess being a prostitute. The tenuous existence of other Sappho is supported by the shaky claim that other Sappho was born in Eresus, instead of Mytileneans, where the Poetess was from. Other Sappho could have been a real person, but she may also have been a later invention meant to polish up the image of Sappho the Poetess, and absorb the malevolent stories put out about her.

This article was edited by Mara Kellogg.

Sources

Sappho: the Complete Works by Delphi Classics

Early Greek Poet's Lives: Shaping the Tradition by Maarit Kivilo (Chapter seven)

"Sappho, Schoolmistress" by Parker N. Holt

"Ancient Greek Wedding Songs: the Tradition of Praise" by Rebecca H. Hague

Sappho-Poetry Foundation

Sappho-Britannica

Sappho-Ancient History Encyclopedia

Sappho-Ancient Literature

Sappho was born sometime between 610 and 620 BCE on the island of Lesbos. She was from the town of Mytilene, or the town of Eresus, where her parents were well-established and respected aristocrats. There is evidence that her father was from Anatolia, which would have made Sappho not entirely Greek.

The theory of Sappho's family being migrants comes from the name of her father, and the spelling of Sappho's name. Her father was named Scamandronymus¹, a name familiar to readers of the Iliad. In the Iliad, the hero Achilles fights the Scamander, the god of the river that surrounded Troy. The name Scamandronymus comes from that minor god. Greeks were not in the habit of naming their children after the gods of rival, defeated kingdoms. And while every generation and nationality has parents who enjoy giving their children "unique" names, it is reasonable to assume that Sappho's father may have come from farther afield. To further support this theory, the spelling of Sappho's name varies, also appearing as Psappha, which has Anatolian origins.

Sappho had three brothers: Larichus, Erigyius, and Kharaxos. Not much is known about Erigyiu--not even his name is certain. Larichus was a handsome and successful young man who served as a cupbearer to a noble family. Kharaxos was, by far, the most colorful of the three. Sappho disapproved of him, as he had fallen in love with Rhodips,² an Egyptian courtesan. They were deeply in love, and if that wasn't disreputable enough, Kharaxos had to turn to piracy to support his passion for the beautiful Rhodips.

Now, it must be noted that the Kharaxos story comes from Ovid, a Roman writer who lived hundreds of years after Sappho. Ovid wrote quite a bit about Sappho, but he was, to put it delicately, full of crap. Any story about Sappho put forward by Ovid should be taken with a large grain of salt. However, in the "Brothers Poem" discovered in 2014, Sappho wrote:

"...But you're always chattering that Kharaxos / comes, his ship with fully stuffed hold. As to that, / Zeus and the gods only know, but these thoughts should / not be in your head.

Instead let me go, having been commanded / to offer many prayers to Hera the Queen, / that his undamaged ship should deliver up / Kharaxos to us

here, finding us safe and serene. And as for / the rest of it, to higher spirits leave it / now, for calm seas often follow after the squalling of a storm..."

|

| Sapphic fragment |

In 604 BCE, Sappho and her family were exiled to the island of Sicily for non-specific political reasons. Sappho's parents were aristocrats with some political clout, and it is speculated that they may have made enemies with the wrong people. They settled in the city of Syracuse. There's no real record of what happened in Syracuse, but the city was later so proud of being the temporary home of Sappho that they later erected a statue of her and minted coins with her face on them.

While Sappho's remaining poetry isn't explicitly political, that Sappho may have written about politics isn't out of the question because so much of Sappho's poetry is lost. In her later life Sappho was a well-respected political figure; when she started talking politics isn't known, but it isn't out of the question that it was pre-exile. It's difficult to say because Sappho was somewhere between six and sixteen at the time of her family's exile.

Sappho's family returned to Lesbos some time in the 590s, and it was then when Sappho married Cercylas of Andros and had one daughter, Cleis, named after Sappho's mother.

Now, Sappho is synonymous with female homosexuality. The term "lesbian" takes its name from Sappho's home island of Lesbos, and the world "sapphic," a word used to describe female homosexuals of all stripes, takes its name from Sappho herself. While many historians and writers have tried to dismiss Sappho's more homoerotic poetry as "just gals being pals," only people reading Sappho in a state of willful ignorance would agree. In her poem "Gongyla," Sappho writes:

"Gongyla, thou golden / Maid of Colophon / Like the breath of morning / Or a breeze from the sea, / Fresh thy beauty smote me, / Virile of the north. / Startled by thy vision, / Transports half divine / Flooded hearts and bosom, / Shook me with desire."

|

| The location of Lesbos (also called Lesvos.) Note the proximity to Anatolia. |

"Dica, Mnasidica, thou art shapely / With the flowing curves of Aphrodite; / ...All thy rays of loveliness concentered / Sun me till I swoon with swift desire."And then, of course, the iconic and completely heterosexual:

"Sweet mother I cannot weave / Slender Aphrodite has overcome me with longing for a girl."

While the above more than demonstrates Sappho's love for women, her sexuality is not definite. While she has become the poster girl for lesbianism, it is just as likely that Sappho was what we now classify as bi or pansexual. There are many men mentioned in the long list of Sappho's lovers, and she did have a daughter. And, don't forget, there was her husband, Cercylas of Andros.

However, "Cercylas of Andros" may be some ancient writer's idea of a joke, as the name of Sappho's husband roughly translates to "Prick of the Isle of Man." It is possible that Cercylas was fictional, an addition from later writers to sanitize Sappho, or, as was popular with later Greek writers, to make fun of her. It is certain that Cleis existed, as Sappho wrote of her:

"Sleep, darling/I have a small/daughter called / Cleis, who is

like a golden / flower / I wouldn't take all Croesus' / kingdom with love / thrown in, for her"Whether Cleis was Sappho's biological daughter, adopted daughter, or a particularly adored niece, it is evident from this fragment that Sappho adored her. This view of Sappho as a mother figure is unsurprising, given the large circle of women Sappho befriended and purportedly mentored.

Sappho had a lot of friends, that much is certain. However, her relationship with them is just as murky and uncertain as the woman herself. Were they friends? Were they students? The true answer is lost to history. Tradition holds that Sappho ran a thiasos, a sort of finishing school for young ladies. Modern theories posit that she was more the hostess of an Ancient Greek salon, or a hetairia.

|

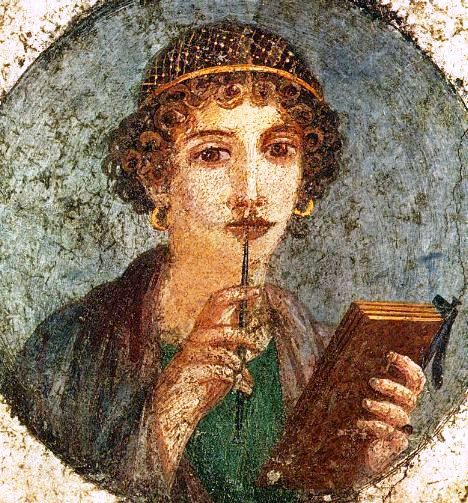

| Aphrodite. Of her, Sappho wrote: "Aphrodite of the foam/Who hast given all good gifts/And made Sappho at thy will/Love so greatly and so much" |

The idea that Sappho held a thaisos comes from the multiple young women she wrote poetry to as her students. Legend holds that her thiasos started out as a type of finishing school, where nobles would send their young daughters to be taught the womanly accomplishments they would need for marriage. However, over time Sappho's school evolved into a cult of Aphrodite and Eros, with Sappho as high priestess.

This theory is supported by the large volume of remaining poetry devoted to Aphrodite. And while there is no definitive proof of Sappho entering the priestesshood, she seems to have exercised an extreme level of devotion to the goddess of love and beauty. The only intact poem of Sappho's is her "Hymn to Aphrodite," and it ends with the provocative:

Now, while this sound like a completely normal thing for a religious person to say, it must be kept in mind that the Ancient Greeks didn't have the same sort of relationship with their gods as believers in Abrahamic religions. The Greek gods were capricious and cruel. Catching their attention ended in disaster 99% of the time.³ Enlisting the help of the gods was done with great caution and great reverence, normally in a temple with the appropriate sacrifices and offerings. This tender, personal entreaty to Aphrodite suggests that Sappho believed that she had a personal relationship with the goddess, priestess or no."All I long for; Lady, in all my battles / Fight as my comrade."

While Sappho may have thought herself to have a connection to Aphrodite, the amount of poetry dedicated to the goddess may exist because Sappho's bread and butter were wedding songs. (As a lyric poet, Sappho's poems were meant to be sung.) Ancient Greek weddings went on for several days, and singing was a major part of the celebrations. Songs comparing the groom to the great heroes of Greek lore, and the bride to the goddess Aphrodite or the infamous Helen were as much a staple of ancient weddings as Mendelssohn's Wedding March or Pachelbel's Canon are of modern weddings. In fragment 27, Sappho wrote:

"Raise high the roof beams, workers! / Hymenaeus! / Like Ares, here comes the bridegroom! / Hymenaeus! / Taller than the tallest men! / Hymenaeus!In a different song, she wrote:

"Bride, of maidens all the fairest image / Mitylene treasures of the Goddess, / Rosy-ankled Graces / are thy playmates;"

|

| Bust of the Poetess |

The idea that Sappho ran a hetairia comes from historians in the 20th and 21st centuries. Instead of running a school, it is believed that Sappho hosted a salon, exchanging artistic ideas with a diverse group of female poets and musicians. Even in this scenario, historical tradition portrays Sappho as being older than the rest of her gal pals and being in a mentoring position. While Sappho almost certainly did some instruction to the women performing her work, like any modern conductor would, there is no definitive proof that Sappho served as a teacher at all. In fact, Sappho's poetry suggests that she was more the member of an informal circle of friends. In a prelude, Sappho wrote:

"Deftly on my little / Seven-stringed Barbitos, / Now to please my girl friends / Songs I set to music"In fragment eleven, she says:

"I will sing this skillfully to please my friends."These lines make it clear that pleasing her friends, and having her friends' approval was important to Sappho, more important than the approval of a student generally is to a teacher. Furthermore, Sappho herself mentions her friends, writing in her poem "Damophyla":

"Sapphics thou has written, / Verses in my meter, / With a skill surpassing / In the melic art."Sappho was clearly not the only poet in her social circle. Where then did this theory of Sappho being a school mistress or intellectual mentor come from? For hundreds of years, it has been an almost indisputable fact. This theory most likely comes from a misunderstanding of female friendships and Sappho's sexuality.

Since history has, until recently, been looked at from an exclusively masculine point of view (stay with me, gentlemen), historical women have been relegated to rigid roles, no matter the fact that women, just like men, are complex and cannot fit into a single defined category. It is easy to put Sappho in a teacher/mother category because of her poetry about her daughter. Her work, in certain lights--especially her work dedicated to her friends--might come off as instructional. However, looked at in a different light, her poems read more like a woman giving her best friend advice. For example, in fragment 75 she says:

"Oh Dica, set garlands upon your beautiful hair, / weaving plant strands with your delicate hands; for / those who wear attractive blossoms will surely / rank first, even among the Goddesses, who frown / upon those without garlands."While more poetic, this has the same cant as a woman giving her friend fashion advice. Sappho goes beyond fashion advice, however. In fragment 66, she says:

"I believe the woman that has your wisdom will / never see the sunlight."This heartbreaking commiseration over the abominable treatment of women in Ancient Greece isn't the end of it. In Fragment 39, Sappho says:

"But to you, Atthis, thinking of me is hateful, as you / flee to Andromeda"This fragment has often been touted as definitive evidence that Sappho ran a school. Her student, Atthis, defected to a rival school run by Andromeda. However, if you scream this poem angrily, it becomes clear that it could also be interpreted as Sappho lashing out angrily at a friend who has betrayed her.

Then there's Fragment 33, which says:

"Foolish woman! Be not proud for a ring."Here's Sappho reproaching a woman for vanity, poor money management, general bitchiness. Without more of the poem it's difficult to say. It is important to notice the subject is referred to as a woman instead of a girl.

Some of Sappho's poetry comes across as downright gossipy. Fragment 73 says:

"More pleasing is Mnasidika than tender Gyrinno"And fragment 74:

"I never found someone more disdainful than you, O Anna."Sappho was clearly excellent at throwing shade.

|

| "Pompe Dressing for a Dionysian Festival" shows the typical Greek fancy dress (or undress) for women. Note the garlands. |

Sappho was often likened to Socrates, a noted pederast. Because of Sappho's equation with Socrates, and because historically society has had difficulty wrapping its collective heads around women and copulation, her sexuality was understood not from a female perspective but from a masculine perspective, and Ancient Greek male sexual norms were ascribed to her for centuries. It is only in recent years that Sappho's sexuality has been looked at from a female perspective.

The assumption of female homosexuality being exactly like male homosexuality brings in the interesting question of pederasty. Among Ancient Greek men, homosexuality was normalized within a pederastic context. An older nobleman found a hot piece of ass he wanted to "mentor," and the pair struck up a relationship. It was assumed that the same would apply to women. However, in no context does Sappho demonstrate a romantic and sexual love for a younger person. In fact, she makes her feelings on the matter quite explicit in fragment 72, saying:

"For if you love me, choose another, younger / spouse, for I will not suffer to live with you, as an / old woman with a young man."Though she is speaking to a man (remember, bi- or pansexual) these lines make Sappho's preferences clear. And while there are poems where Sappho describes her love for a "maiden", there were several different Greek words for love, and this should not be taken as sexual love.

Furthermore, when Sappho does describe a "maiden" in a sexual way, it's a maiden with another maiden, not with Sappho herself. In her poem "Telesippa," Sappho writes:

"Sleep thou in the bosom / of thy tender girl friend,/ Telesippa, gentle / Maiden from Miletus"The poem goes on to become more sexually explicit, saying:

"Warm from her desireful / Heart the flush of passion / On your cheek unconscious, / With her sighs shall deepen. / All the long sweet night-time, / Sleepless while you slumber, / She shall lie and quiver / With her love's mad longing."Telesippa is clearly engaging in an affair but with a person of her own age. Sappho doesn't project herself as Telesippa's lover, nor does she act the part of the voyeur. In fact, the poem could almost be seen as Sappho giving Telesippa a pep talk, assuring her of great things to come.

Whatever the dynamic of Sappho's friend group, Sappho garnered fame throughout the ancient world and not for her "school." She was referred to as "the poetess," an allusion to Homer, who was frequently called "the poet." This epitaph demonstrates that, in her own time, Sappho was though to be on par with Homer, who continues to remain the most influential male poet of antiquity.

Her fame was well deserved. Sappho was the vanguard of a new type of poetry, lyric poetry. Personal, introspective, and meant to be sung, lyric poetry was a big departure from epic poetry, which had been the zeitgeist for decades previously. In modern terms, Sappho was more of a singer-songwriter than a poet.

Much of Sappho's poetry was set in what we now call "Sapphic meter," which consists of four lines--three long, the last short. The combination of stressed and unstressed syllables⁴ gives Sappho's poetry a distinct character that has been copied over and over again since she conceived it.

|

| Woman playing the pectis |

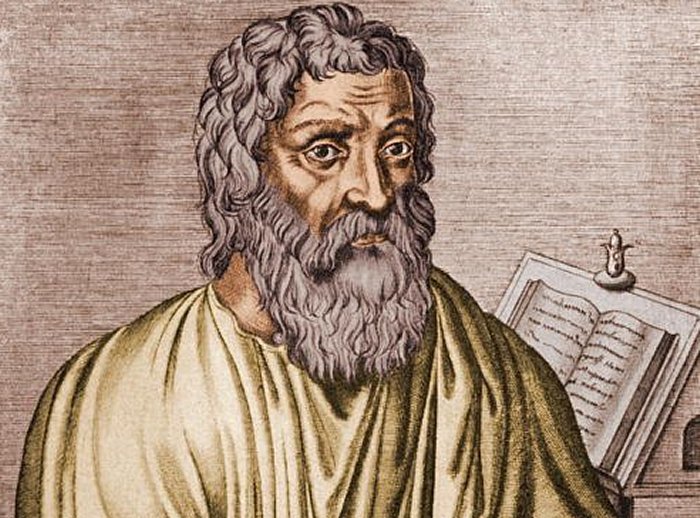

There are two theories put out about the end of Sappho's life--the plausible and the dramatique. The plausible theory is that she died of old age in the 550s. The more theatrical story, put about by our old buddy Ovid⁶, is that, distraught over her unrequited love for a man named Phaon. This incident is referred to as the "Lucadian Leap," and appears multiple times in Greek mythology.

The connection of Sappho with the Lucadian Leap may have been an attempt at humor. It could be that this story of Sappho, a known homosexual, throwing herself from a cliff for love of a man could have been an attempt to satirize romantic love. Or an attempt to make fun of Sappho and her overblown love of love. Or, it's possible that when talking about the Lucadian leap, later writers weren't even talking about the Poetess Sappho of Lesbos, but instead another Sappho who was a courtesan working on Lesbos⁷.

Sappho was well respected during her lifetime. As mentioned, she was placed on the same level as Homer. Several of her turns of phrase entered Ancient Greek as common expressions. Phrases like "love, that sweet loosener of limbs," "I am of two minds," and "more golden than gold" entered the vernacular.

The philosophers Plato and Solon were big fans of hers. Solon, who wasn't known for his displays of emotions, reportedly:

"...heard his nephew sing a song of Sappho's over wine, and since he liked the song so much, he asked the boy to teach it to him. When someone asked him why, he said: so that I may learn it, then die."Plato referred to her as "the tenth muse." Even Ovid gave her credit, saying, "What did Sappho of Lesbos teach girls but to love?"

|

| The tale of the Lucadian Leap may have originated from this myth about Aphrodite. |

A lot of the myths swirling around Sappho come from stories put around by New Comedy writers after her death. Her sexual habits were exaggerated and mocked. She was dismissed as a licentious deviant. This led to her work being banned by Roman censors and burned by Pope Gregory VII.

Much of Sappho's work is lost, not just because of censors and the tragic loss of the Library of Alexandria, but because Aeolic, the dialect of Greek Sappho wrote in, is incredibly difficult to translate. Even a few centuries after her death Sappho was a hard read, so her works weren't constantly transcribed like the works of other writers. However, archaeologists are still digging up new Sapphic fragments. Her poetry has been found in the wrappings of Egyptian mummies, and occasionally turns up in the collections of private individuals. With any luck, new Sappho poems will keep turning up, and our knowledge of this pioneering poetess will continue to grow.

In fragment 30, she predicted:

"I believe men will remember us in the future."She certainly wasn't wrong.

|

| Sappho, by John William Godward |

¹Or Scamander, Simon, Eunomius, Eumenus, Eerigyus, Erigyius, Ecrytus, Semus, Camon, or Etarchus. Sources disagree, but Scamandronymus is the most common.

²Rhodopis is also sometimes known as Doricha.

³Artistic license has been taken with the statistic, but, despite not being based in actual fact, 99% probably isn't too far off.

⁴For a much better, and painfully exact description of what Sapphic Meter is, click the hyperlink.

⁵For more information about modes, go here for a comprehensive explanation.

⁶This theory may have also originated from the Greek dramatist Menander, or the Roman writer Lucian.

⁷However, the existence of other Sappho is also disputed. She is often used to explain later stories of Sappho the Poetess being a prostitute. The tenuous existence of other Sappho is supported by the shaky claim that other Sappho was born in Eresus, instead of Mytileneans, where the Poetess was from. Other Sappho could have been a real person, but she may also have been a later invention meant to polish up the image of Sappho the Poetess, and absorb the malevolent stories put out about her.

This article was edited by Mara Kellogg.

Sources

Sappho: the Complete Works by Delphi Classics

Early Greek Poet's Lives: Shaping the Tradition by Maarit Kivilo (Chapter seven)

"Sappho, Schoolmistress" by Parker N. Holt

"Ancient Greek Wedding Songs: the Tradition of Praise" by Rebecca H. Hague

"Sappho's Company of Friends" by Anne L. Klinck

"Sappho's Prayer to Aphrodite" by A. Cameron

Sappho-Poets.orgSappho-Poetry Foundation

Sappho-Britannica

Sappho-Ancient History Encyclopedia

Sappho-Ancient Literature